If “Content is King” then perhaps it’s time for a coup

This is by no means an unusual occurrence, but over the weekend I witnessed an argument on Twitter. The subject of the argument was the nature of “content” and whether or not it was desirable. One side of the argument — a fellow games writer and friend of Rice Digital, and someone whom I would tend to agree broadly with even if he wasn’t a friend — argued that overemphasis on “content” is ruining the concept of games as art, while the other, a game developer, argued that players demand “content”.

I won’t name the individuals in question as I don’t particularly want to send people with strong feelings on either side of this subject their way, but I think it is a concept worth discussing. So let’s explore it a bit.

The developer’s initial argument was that game developers and critics underestimate the appeal of games with “a shitload of content”. They went on to argue that players “crave” that — and, moreover, that there aren’t a lot of games in either the indie or triple-A spaces that provide that.

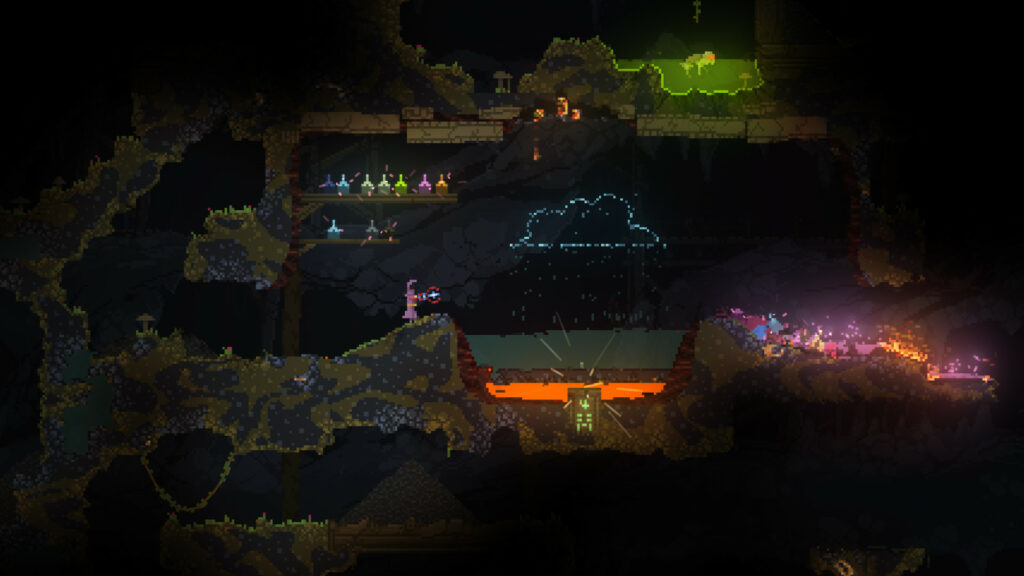

I mean, for starters, this is based on a flawed assumption, since there are myriad games in both the indie and triple-A spaces that are massively bloated with “content”. In the indie space, you simply have to look at any game that makes use of procedural generation — physics-based 2D wizarding sim Noita appears to be one of the most popular recent examples — to find an experience whose reviews proudly proclaim that you’ll almost certainly never see everything of. And mindless “content” delivery systems make up a significant proportion of triple-A gaming these days — particularly those in the multiplayer space, with Fortnite being the most obvious example.

But I digress. The games writer’s response to this was that the overemphasis on “content” in video games today is damaging the medium as an art form by developing increasingly unreasonable expectations among consumers — and pushing those who make deliberately compact, self-contained experiences somewhat to the side.

The concept of “content” as we understand it today largely stems from Bill Gates’ 1996 essay “Content is King” (archived here on Medium), in which he posits the future of the Internet as “the multimedia equivalent of the photocopier, [allowing] material to be duplicated at low cost, no matter the size of the audience” and a place that “allows information to be distributed worldwide as basically zero marginal cost to the publisher”.

Gates argued that “if people are to be expected to put up with turning on a computer to read a screen, they must be rewarded with deep and extremely up-to-date information that they can explore at will” and that “they need an opportunity for personal involvement that goes far beyond that offered through the letters-to-the-editor pages of print magazines”.

He also argued that “content providers must be paid for their work” and that, as of 1996, “it isn’t working yet, and it may not for some time”. He then goes on to make the woefully and hilariously incorrect assumption that “as connections to the Internet get faster, the annoyance of waiting for an advertisement to load will diminish and then disappear”, apparently not predicting the fact that advertisers will use those faster connections to deliver increasingly intrusive ads to people through pop-overs, autoplaying video ads and all manner of other shit.

Gates has a few solid ideas in the essay — most notably that those who are creating things deserve to get paid for their work, much as they would have been in more traditional creative industries such as print — but there’s zero consideration of quality or artistic vision. It’s all about quantity of “content” — and it’s all about the supposed “interactivity” that people desire.

Fast forward to 2022 and these two factors lead to a number of rather undesirable consequences.

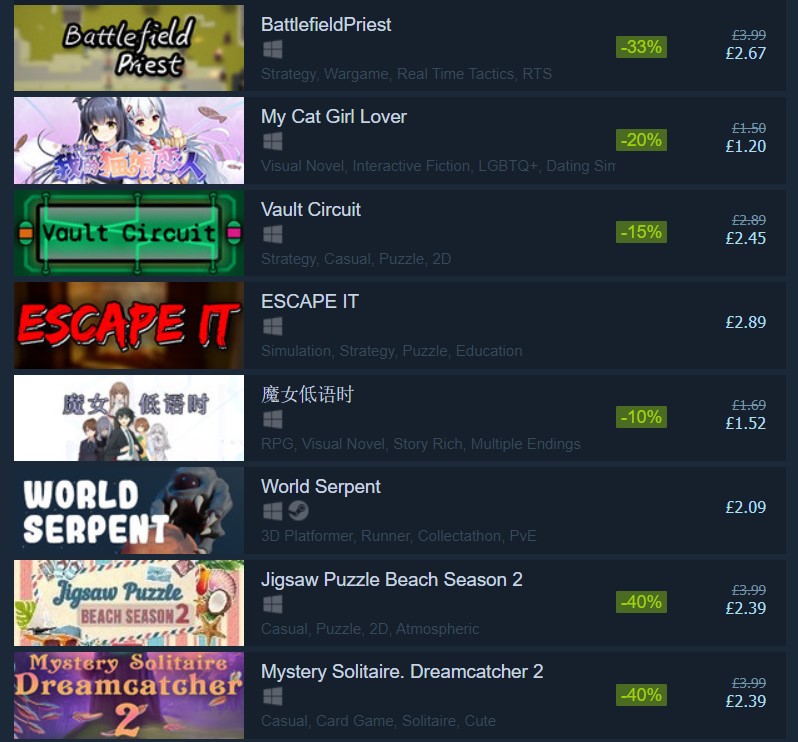

The pursuit of a vast quantity of “content” — more than traditional industries would ever be able to pump out — leads to an oversaturation of the market with low-quality pap, which in turn goes on to drown the actually worthwhile projects which are genuine labours of love that deserve to succeed. You only have to look at the New Releases page on Steam or the Switch’s chaotically disorganised eShop to see this already happening.

And the media covering these things doesn’t help, either. When a pointless “clock” app appeared on the Switch eShop, news sites the world over were covering it because they thought it was amusing, and because they thought it would bring in the clicks to their website. Everyone would have been better served if we had simply ignored the clock app and instead focused on the creative games that had been released that week — because there would almost certainly have been at least one which deserved some attention.

From another angle, the supposed desire for a vast quantity of content leads to another consequence for individual works: the way in which they end up feeling unfocused and ill-defined. Sure, on paper a game with several thousand possible abilities to use for your characters sounds absolutely great — but how many of those abilities are going to be truly unique? How many of those abilities have been thoroughly tested and balanced? If games with deliberately limited numbers of abilities — MMOs and fighting games, for example — struggle to balance themselves effectively, even over the course of years sometimes — how can we expect a game with thousands of abilities to be well-balanced and fair?

And this is just considering the mechanical perspective. Even if a game chock-full of mechanical “content” is polished to a fine sheen, what about the narrative? Is the game really able to say something meaningful if the emphasis is on playing repeatedly for hundreds of hours in the vain hope of eventually seeing everything?

This isn’t to say that all games need a significant narrative component, of course — but if we take into account the supposed desire for a “shitload of content”, where does that leave narrative-centric games with a deliberate sense of beginning, middle and end? Are they somehow “inferior” now for deliberately limiting their length to however long the story needs to be? Should developers of these games be expected to remain chained to single projects forever, churning out new “content” for their narrative games even if they consider their stories to be finished?

Well, that brings us on to the second main point: the desire for interactivity. Games, of course, are already interactive, but that’s not what Gates meant in Content is King. He was referring to a feeling of “personal involvement” in “content” that is available online — that is to say, people should feel like they are part of the “content” they are immersing themselves in.

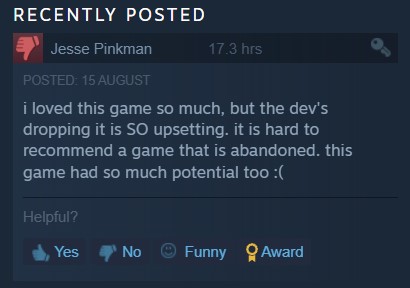

It’s not hard to see where this philosophy has lead us in the modern age: an almost comically obscene level of entitlement. You just have to look at your average Steam review to see people who think they know better than the developers; you just have to look at Twitter to see loudmouthed teens crying about Genshin Impact; and sadly, you never have to look far to see groups of people harassing and dogpiling developers and publishers for making decisions that they, the audience, disagree with.

The justification for this is usually to quote the line “the customer is always right”, commonly attributed to American entrepreneur Marshall Field, but as anyone who has ever worked in retail knows, that is complete bollocks. “The customer is always right” isn’t meant to encourage service providers to unquestioningly cater to customers’ every possible demand, no matter how unreasonable — it is, instead, intended to encourage them to take requests and complaints seriously until such a point that they are in a position to make an informed decision about them.

In other words, “the customer is always right” doesn’t mean that “customers can shout and scream until they get their way”; it means “those providing something to a customer are obligated to listen to what they’re shouting and screaming about, but then are perfectly free to make their own decisions about what to do next, up to and including absolutely nothing”.

The trouble is, that last bit isn’t always taken to heart by either customers or game developers. If a game comes out that is very obviously complete, but which customers think “should” have an update to add “more content”, then if the developer doesn’t follow through on those demands, they’ll get pelted with bad reviews for it being an “abandoned game” or a “dev who doesn’t listen to consumers” or suchlike.

Online platforms don’t help with this either, particularly mobile storefronts; over the last few years, numerous indie developers in particular have reported that if their games do not receive regular updates on both Apple’s App Store for iOS and Google Play, they will simply get removed. This is presumably to ensure that all currently available apps work on current versions of the respective operating systems — but if there’s nothing that actually needs updating, developers are pressured into adding some sort of “content” to their work to ensure they can simply keep selling their product.

The result is a world in which so many projects feel perpetually unfinished; in which you can pick up a game that came out two years ago and still have to download an update before you can play it; in which even supposedly “complete on cart/disc” limited run releases of games still end up getting updates long after they were supposed to be archived.

It hopefully shouldn’t be difficult to see how this ties in with the concept of games as art. If nothing is ever “finished” because of the constant demand for “a shitload of content”, then nothing is permanent and will never be in a suitable position to be put on display or held up as a historical example of something in years to come. How, after all, do you preserve something that was supposedly “complete”, but which subsequently went through a multitude of revisions, only some of which have been kept in a form that can vaguely be called “permanent”?

One could argue that earlier works of art went through a similar revision process: classic novels and plays were rewritten and edited; paintings were refined and adjusted; pieces of music were rearranged and reorchestrated. The difference in all of those cases is that pretty much all of those revisions — with a few notable exceptions — occurred behind the scenes before the work was “released”.

There was no interference from the audience demanding that Mozart change his Fantasy in C Minor for piano to actually be in B flat Major because otherwise it was a bit bleak. No-one told Picasso to change his paintings because the faces looked a bit weird. No-one berated Bizet for not adding an additional act to Carmen two years after it was first performed.

I hunger and long for something quite simple: not games with “a shitload of content”, but rather games that I can just pick up, buy and play safe in the knowledge that they are complete — and that I will be able to experience everything they have to offer to my satisfaction. I’ve reached a point where I simply don’t want to even start games like Noita because I just don’t see the point; that “shitload of content”, rather than feeling like being good value, just makes the experience feel empty, meaningless and devoid of artistry.

Your mileage, as ever with matters of opinion, may of course vary — but for me, content hasn’t been king for a very long time. Instead, all I want is the simple opportunity to enjoy the creative visions of a variety of artists from all over the world — something which we didn’t seem to struggle with all that much before the Internet came along and fucked everything up.

Header image by MidJourney Bot.

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023