Project Lux and VR as the future of theatre

I’ve had a copy of Project Lux on my shelf for a while now; Limited Run Games did a physical release a while back and, as a PlayStation VR owner, I wanted to have it on my shelf because it sounded interesting and physical games are cool.

I have to be in the right mood for virtual reality gaming, though; in my house, an optimal VR setup involves clearing a bit of space in the living room, setting up a fan blowing cold air (otherwise my glasses inevitably steam up inside the headset) and having a clear head that isn’t even a little bit likely to develop a headache at any point in the process.

As it happened, last night featured as optimal conditions as I was likely to get for a long time, so I decided to sit down and check out this intriguing-sounding experience. And I’m glad I did, because it was a really interesting use of VR that I think deserves further investigation from developers with the resources to do so. Let’s talk a bit more about it, then.

For the unfamiliar, Project Lux describes itself as a “VR anime”, and is developed by Spicy Tails, a studio run by Spice and Wolf author Isuna Hasekura. Spicy Tails has made it its mission to take people “into the 2D world, to meet our favourite characters”, and to that end has developed titles like Project Lux and Spice and Wolf VR as bold experiments in the world of immersive storytelling.

The concept of Project Lux is that you are a juror in a futuristic court case. The crime is murder — though who has actually been killed is not immediately revealed — and your job is to relive the events which led up to the murder through the eyes of a key witness: a government agent who had been interacting with a young woman named Lux.

Project Lux’s futuristic setting is a world where the majority of humanity has fully embraced the digital age by fitting themselves with “cyberbrains”. This technology allows humanity to connect directly with one another, share memories and knowledge, and — in theory at least — means that everyone inherently understands one another. It also allows humans the flexibility to abandon their physical, biological bodies and transfer their consciousness into mechanical cyborg bodies for added flexibility and safety.

As we join the narrative of Project Lux, we’re led to believe that although there’s a certain Utopian aspect to the digital immersion of the setting, there’s also a sense of dissatisfaction; individuality has been eroded, and it’s clear that the concept of emotions is becoming harder and harder to grasp for many people, including the government agent whose body we inhabit for the duration of the narrative. This makes Lux, one of the few people out there who has deliberately chosen to remain fully human, something of an intriguing anomaly — and someone who is potentially valuable.

From hereon, the narrative unfolds as the government agent attempts to inspire Lux into developing works of art based on various emotional stimuli — both intentionally and unintentionally triggered. Over time, it becomes apparent that Lux’s work is having an impact on the digital world, for better or worse — but Lux also comes to some critical realisations about herself, and about the idea of individuality in an increasingly homogeneous world — and a world which places undue pressure on people to conform, no less.

What’s interesting about Project Lux is that the very medium through which the story is delivered becomes part of the story itself. In order to experience the narrative, you have to abandon your own individuality, and accept that for the duration of the story, you are inhabiting the body of this government agent, seeing and hearing what he sees and hears rather than living life for yourself. And the fact that the limitations of VR leave three senses unaccounted for does not go unnoticed by the narrative, either; in fact, one of the two possible endings plays with this idea in a very clever way.

This, of course, raises some interesting questions. You are not the government agent, yet the immersive nature of VR provides you an interesting sensation that, while not completely realistic, definitely triggers some of the same natural responses when confronted with strong stimuli — as if you were actually there. Throughout the narrative, you’ll experience this in several ways when Lux touches “your” face, hugs you — and in one memorable moment, appears to have a seizure while you watch, helplessly, unable to move.

At some point during your time with Project Lux, you’ll doubtless notice that what you’re experiencing is not really a game, not really a visual novel — not even really an anime. Instead, what you’re actually being part of is a form of theatrical production, only one where you’re not sitting in the audience watching from afar; you instead have the unique opportunity to sit “inside” one of the characters and observe everything that is going on from the very middle of the action.

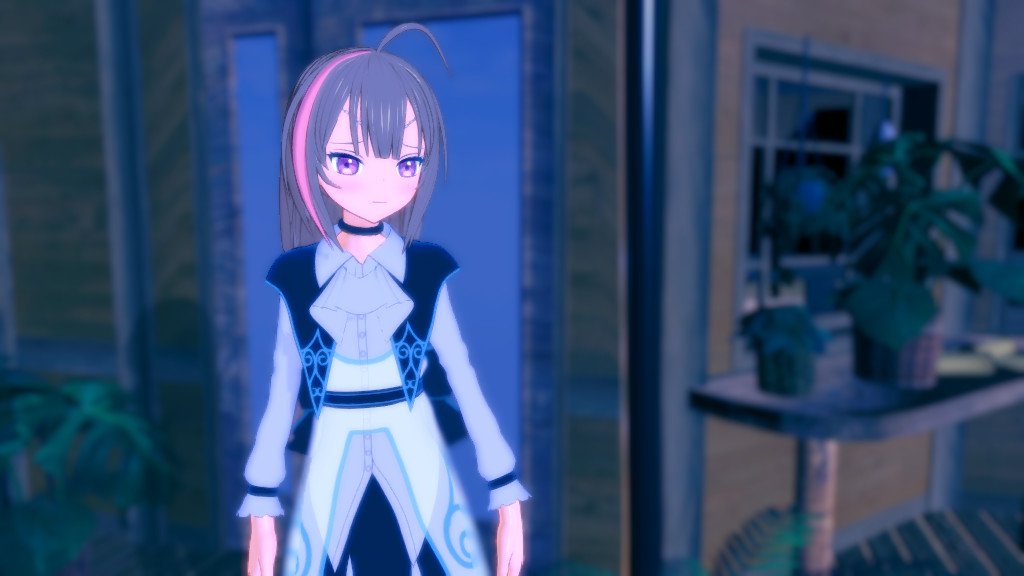

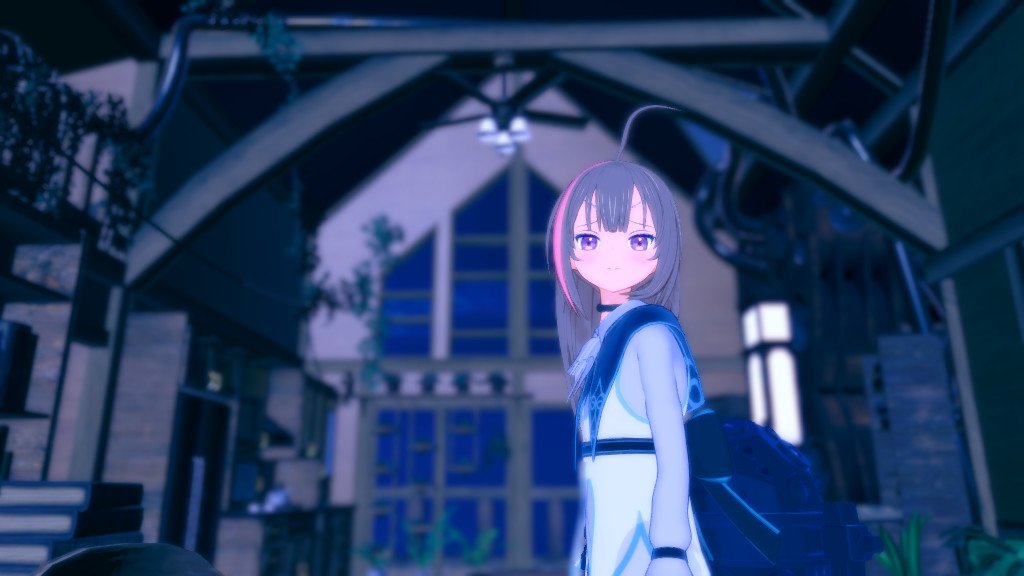

And Spicy Tails was well aware of this, too; while the game unfolds in a very deliberately limited range of environments — much like a theatrical production — and “you” don’t move around all that much, a lot of love, care and attention has been spent on making Lux look and feel like a “real” person, despite obviously being an anime-style character. Her motion capture is convincing; her body language as she delivers her speeches tells you as much as the script does; she feels very “human”.

By contrast, the protagonist character is deliberately very rigid — and a stark contrast to Lux. His voice is monotone and emotionless; his cyborg body is dressed in a fairly nondescript business suit; he rarely moves during any of the scenes; and the enormous height disparity between him and Lux when he’s standing up only serves to highlight what completely different worlds the pair of them live in.

The result is remarkably akin to the experience of watching a “two-hander” theatrical production, where the entirety of the story is delivered through the dialogue between the two main characters. We hear of other things happening, but we never see them; all that matters is us — and Lux.

As a relatively early example of the VR medium being used to deliver a story in this manner, Project Lux isn’t perfect; there are still lessons to be learned, after all, both by the developers of such experiences and those localising them. And, of course, the very nature of this experience means that it’s not for everyone; if you’re not into sitting still for an hour listening to people talk in Japanese, you probably won’t dig this.

Notably, while the game can provide a fully immersive experience if you’re fluent in spoken Japanese, turning on the subtitles means you have a slightly obtrusive semi-opaque text box at the bottom of your vision for the entire time you play; it would have been nice to see the subtitles simply “floating” in the game world, though presumably the text box was added to ensure they would be readable regardless of where you are looking.

More egregious from a localisation perspective is that there are a couple of scenes where the subtitles are completely absent. There are some conversations where you’ll hear the government agent speaking in Japanese, but the text translating what he is saying simply doesn’t move on from the last thing Lux said. This isn’t a major problem for the story as a whole as you can usually figure out what was said from Lux’s subsequent responses, but it’s still a little jarring when it happens and could have probably been avoided with a more rigorous QA process.

But discovering lessons to be learned is an important part of establishing a new medium and a new way of doing things — and Project Lux is definitely an intriguing look at a possible future of how some theatrical productions could be handled in the future. Nothing will ever quite replace the experience of going to an actual theatre, of course — but being able to experience a small-scale, very personal narrative like this from a first-person perspective, right in the middle of things is definitely something worth exploring further.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that producing narratives like this in the digital space allows for the flexibility to do things that are completely impossible in reality. While it’s certainly possible for theatrical productions to have a “style” about them, they’re still inherently limited by the physical world — and the inherent limitations of flesh-and-blood human beings. Make a story that unfolds fully in the digital world, however, and your main characters can be anime girls; your environments can be fantastic and change at a moment’s notice; you can explore all sorts of things that you simply can’t do on stage.

Perhaps we’re already further into the future depicted in Project Lux than we’d like to admit. Still, if we’re all stuck indoors, we might as well have some fun, right?

Project Lux is available for PC VR devices via Steam, and PSVR via the PlayStation Store.

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023