The sound of footsteps: delving deeper into Resident Evil Zero

It took me nineteen years to finally beat Resident Evil Zero; I picked the game up back on its original GameCube launch, played through the initial “train” section, then for one reason or another, never progressed any further.

Part of the reason for this was the fact that the early train section had already frustrated me a bit with its “tank” controls — which really didn’t feel good on the GameCube controller with its tiny D-Pad — and I was skeptical as to whether or not I’d be able to take on the rest of the game’s challenges with such a cumbersome method of getting around.

I tried again a few more times over the years, but always found myself feeling that same frustration; despite the tank controls making sense in theory, I never quite felt like I was truly in control of protagonists Billy and Rebecca, and thus any time I ran headlong into combat with a challenging enemy, I’d end up taking damage or dying in a way that I didn’t tend to feel was entirely my fault.

Thankfully, the more recent HD ports of Resident Evil Zero, as we saw last time, add a direct-control analogue system to the mix — and make it the default. You can still play with tank controls if you’re a traditionalist and/or masochist, but the addition of the analogue control scheme alone makes the more recent ports of Resident Evil Zero the definitive versions so far as I’m concerned. (And with a proper analogue control scheme having been a thing in survival horror since 2001’s Silent Hill 2 on the PlayStation 2, there really was no excuse for Resident Evil as a whole to have not adopted it sooner.)

I’m glad I finally made the effort, though, because Resident Evil Zero is actually a very fine example of classic-era Resident Evil — and its unique mechanics that we talked about last time add some interesting twists on the usual formula, particularly when it comes to making use of both characters to solve puzzles.

It’s fairly common knowledge these days that old-school survival horror is based heavily on the idea of making the player feel vulnerable, and that this is primarily achieved through deliberately limiting the player’s resources. Having not really played a classic survival horror game for many years, however, I’d forgotten what this really meant in practice: a constant sense of unease that you wouldn’t have enough ammunition to take on the as-yet unknown challenges ahead of you, or that you’d used up all the healing items available a little too willingly and would end up putting yourself in an unwinnable situation.

Make no mistake, it absolutely is possible to put yourself in an unwinnable situation in Resident Evil Zero; there’s a reason why when you reload a saved game you have the option to restart from the beginning. But once you start to figure out exactly how the game works, you start to get a distinct feel for how you “should” be handling various situations, and it’s markedly different to modern games with a similar look and feel. There’s a certain amount of flexibility, but for the most part, the game demands that you make some quick decisions — and that you bear the abilities of both playable characters in mind when you make those decisions.

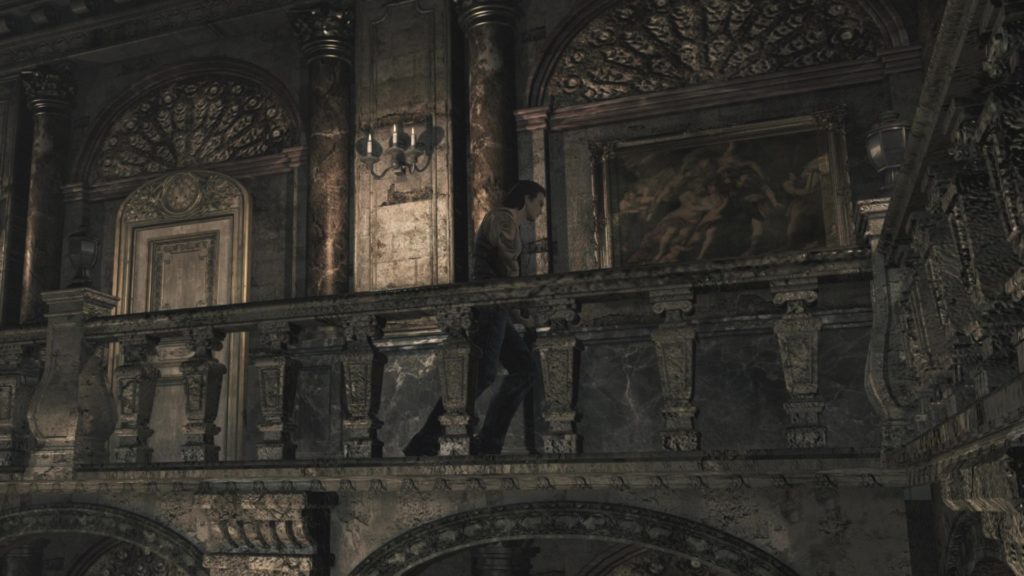

Take a sequence which occurs when you finally unlock the basement to the mansion-like training facility that Billy and Rebecca find themselves in after successfully “stopping” (crashing) the train in the first segment of the game. After descending some stairs, you enter a long corridor which has three absolutely enormous spiders in it. Each of these spiders takes a fair few bullets to kill, just like everything else in Resident Evil Zero, and has the potential to inflict the frustrating Poison condition on your characters.

You could kill all the spiders, but by this point in the game you’re likely already hurting for ammo a bit, so it’s a risky move. Instead, a much better option is to take control of Billy and Rebecca separately, then simply run through the corridor with each of them one at a time, avoiding the spiders entirely. Big, hairy and scary they may be, but they’re also surprisingly sluggish to respond, meaning if you don’t stop you can easily avoid their attacks — particularly with the new control scheme.

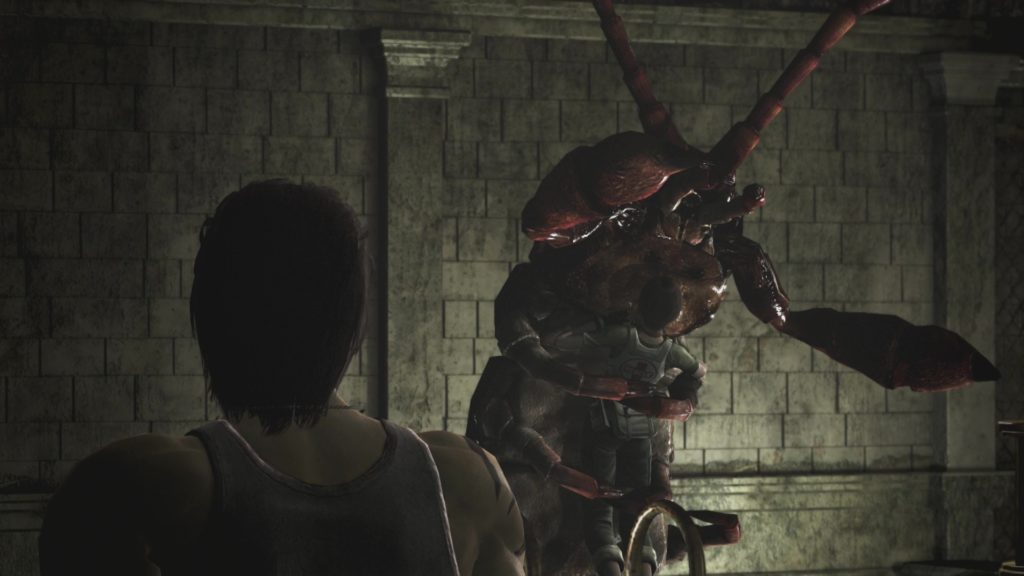

There are numerous situations like this throughout the game, particularly involving the “humanoid leech” enemies that have an extraordinarily long reach and acid attacks. These things are best dispatched with three Molotov cocktails to the face, but assembling Molotov cocktails involves finding empty bottles and gas cans, making sure you have space in your inventory to carry both of those things, then combining them together to produce the weapon itself.

Then, of course, you have to make sure you hit the humanoid leech with your throws, preferably without taking damage and after they’ve “transformed”. But once again, if you know a humanoid leech is lurking in a particular location — and you’ll know this before you see them thanks to the game’s excellent audio cues — you’re generally better off just taking each character through individually and charging past them; their humanoid stature means that both Billy and Rebecca can actually barge them out of the way if they’re obstructing somewhere you need to be or an item you need to nab.

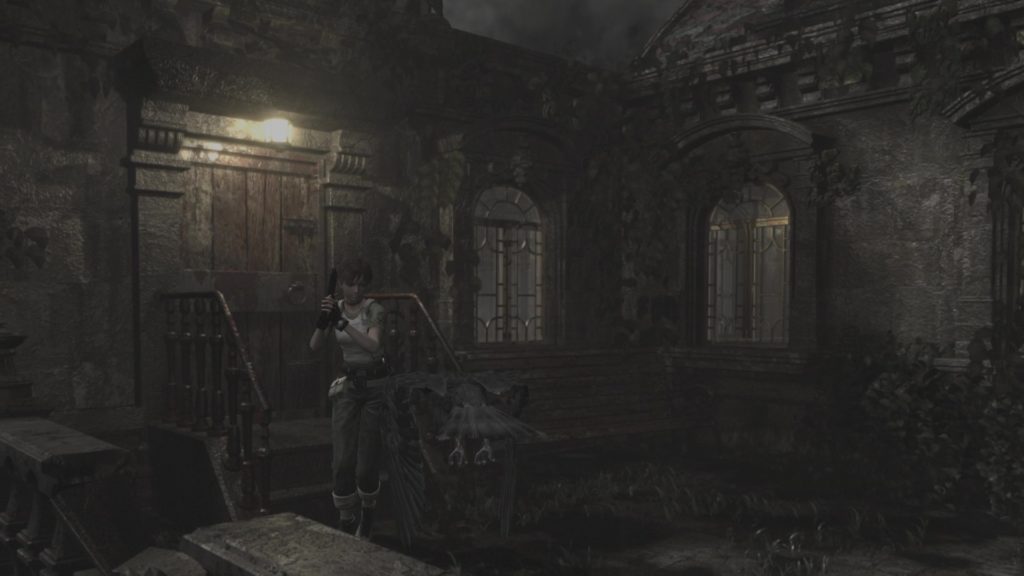

This sense of getting your head down, closing your eyes, charging past something absolutely terrifying and not looking back is absolutely classic horror — not to mention the stuff of childhood nightmares — and every time it happens it’s a stark reminder that neither Rebecca nor Billy are superheroes. They’re in constant danger, and thus when the choice between fight or flight arises — as it does so frequently — the latter is generally the preferable option if at all possible. It’s something that early-era Resident Evil always did very well, and it’s an especially prominent part of the Resident Evil Zero experience.

Unfortunately, this also highlights a particular weak point of the early Resident Evil titles: the points where you’re forced into combat against a boss enemy in order to proceed. This happens on seven separate occasions in Resident Evil Zero, and it’s a chore every time. There’s no real strategy to each fight beyond “move out of the boss’ reach, then hit them with the most powerful weapon you have”.

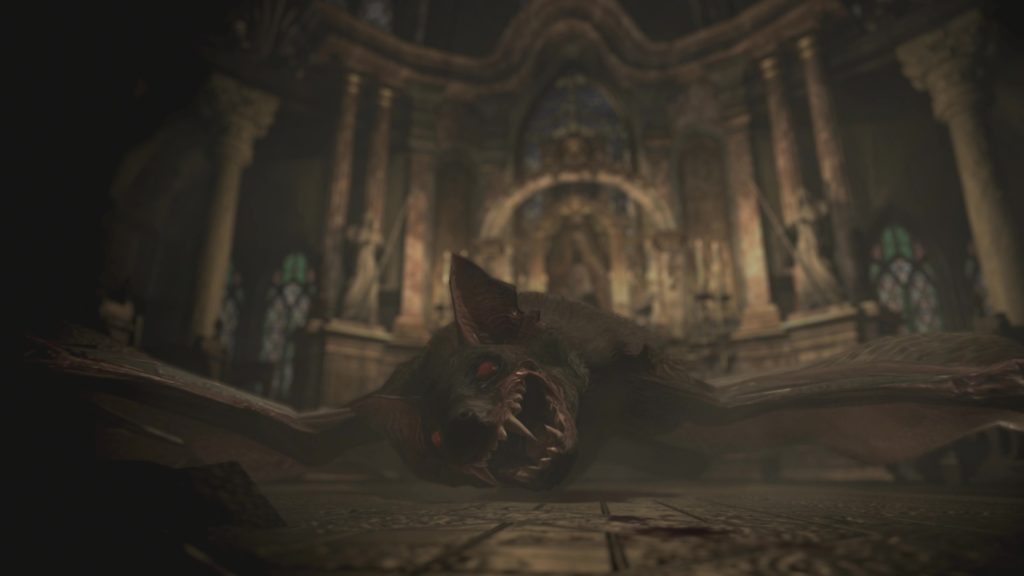

A particular lowlight for many veterans of Resident Evil Zero is a confrontation against a giant bat in an abandoned church; while visually striking, this boss fight is awkward and cumbersome to fight with the prerendered camera angles, and the fact that said boss summons swarms of smaller bats to harass you — often preventing you from getting a shot off at all if you’re unlucky — just makes the whole encounter feel like it takes more luck than skill to get through.

That said, the actual final boss confrontation subverts the expectations set by the previous encounters very nicely in that you can’t defeat it by sheer brute force at all. Instead, playing as Billy, you simply have to hit the boss with any weapon enough times that you distract it from pursuing Rebecca, who is automatically running around the room to operate several pieces of machinery at this point. The battle then becomes a simple matter of survival rather than trying (and failing) to be an out-and-out action game — and it feels infinitely more fitting with the vibe of the rest of the game as a result.

Let’s switch gears now and talk about another important part of the Resident Evil series as a whole — a particularly pertinent discussion due to the fact that there has been some ill-natured murmuring over the relatively short length of newest title Resident Evil Village in recent weeks.

When I cleared Resident Evil Zero for the first time, the clock read just over 8 hours. That’s short for a modern game — but what that timer doesn’t take into account is the number of times I died and had to retry a segment, or the times I deliberately reloaded in order to try and complete a section a bit more efficiently by taking less damage or using less ammunition. The actual figure is probably closer to 12 hours or so — still relatively short, but a little more “acceptable” in the eyes of some modern gamers.

That’s not where the Resident Evil Zero experience ends, though. Instead, classic survival horror is built with replay value in mind, and to that end there are a number of different things you can do once the credits roll. Firstly, you can simply replay the game in an attempt to do it more quickly, since faster completions unlock new weapons for Rebecca and Billy on subsequent playthroughs — clearing the game on Normal or Hard in 3 hours 30 minutes or less unlocks a rocket launcher for Rebecca and a sub-machine gun for Billy, for example.

On top of that, simply clearing the game unlocks a new mode called Leech Hunter, in which you take control of Billy and Rebecca in an attempt to locate as many coloured Leech Charms hidden around the game environments as possible. Leech Charms cannot be dropped once you’ve picked them up, meaning your inventory space gradually dwindles the further you go, and to make matters even more complicated, Billy and Rebecca are only allowed to pick up one particular colour of Leech Charm each.

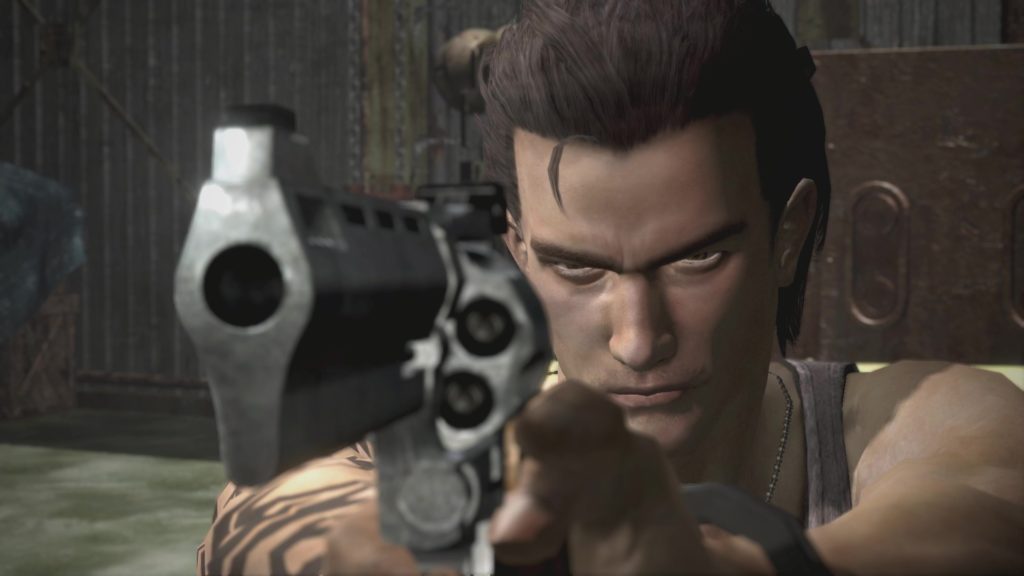

Leech Hunter is worth engaging with if you fancy attempting to speedrun the game, as achieving a good score in it allows you to unlock infinite ammo for various weapons, as well as the Magnum Revolver that is only otherwise seen during the ending cutscene. It also provides an interesting, gameplay-centric variation on the experience, challenging you to make use of all the skills you developed in the main story mode in order to achieve your goals.

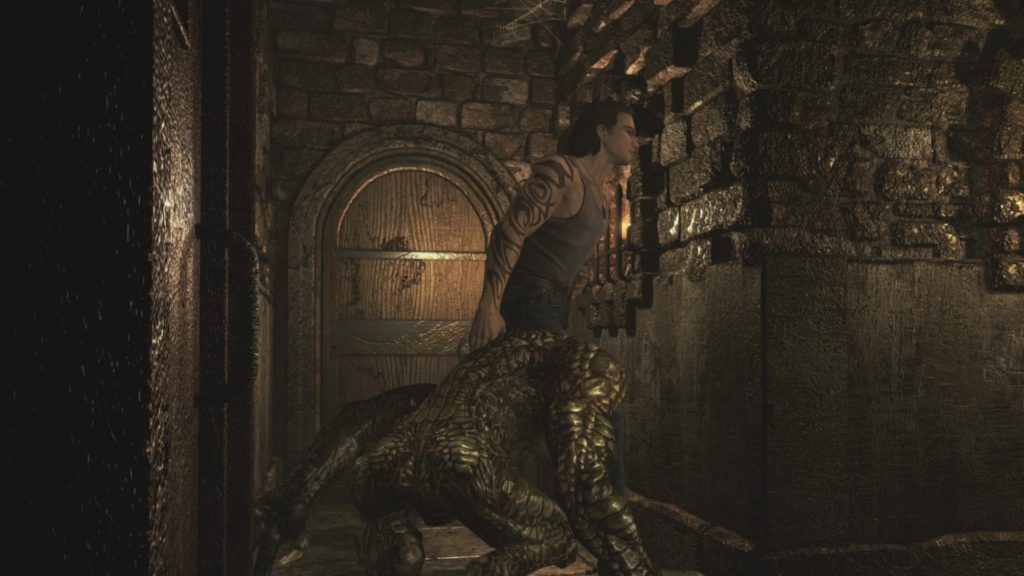

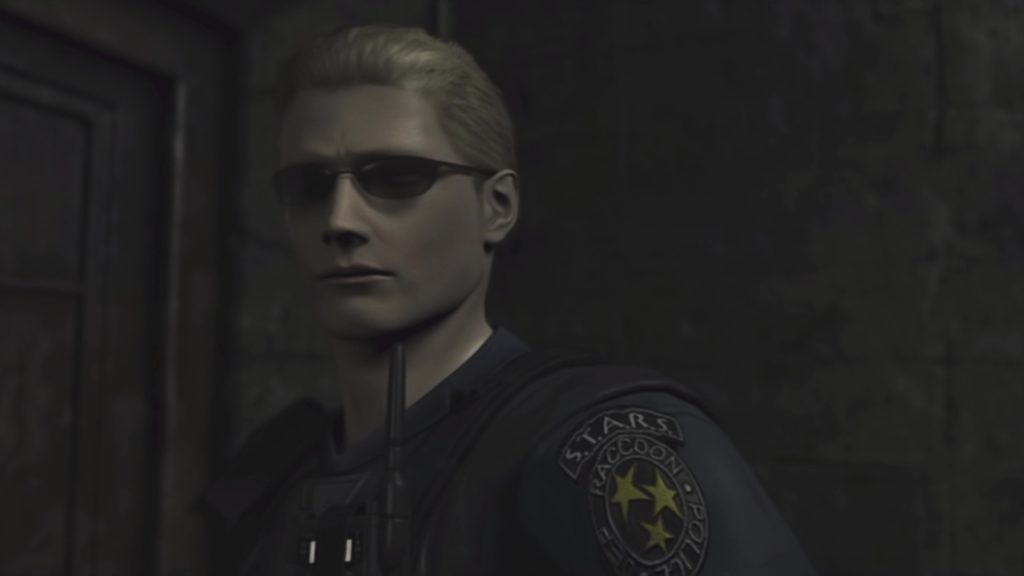

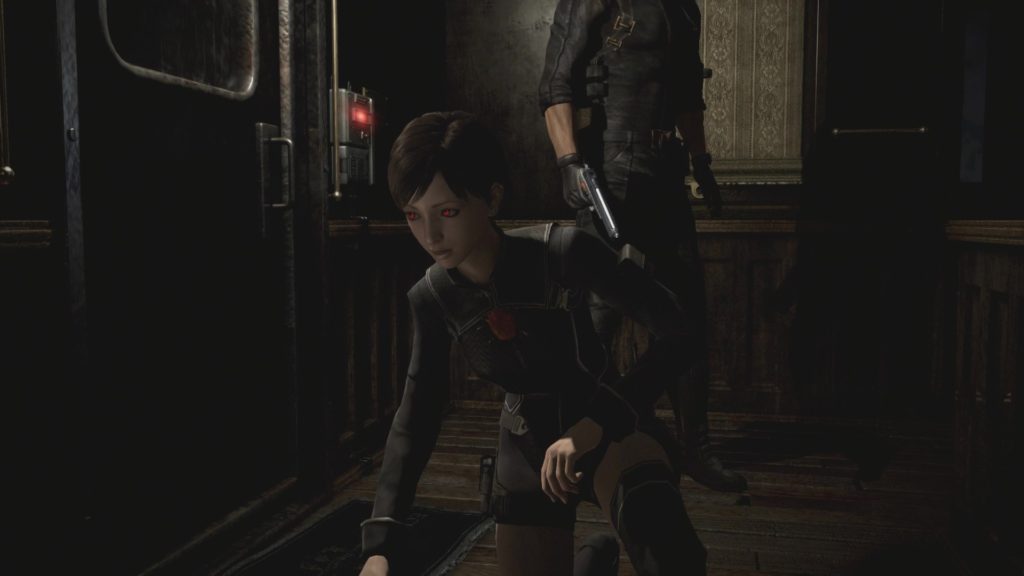

The recent HD remasters of Resident Evil Zero add one more bonus to the mix, too: Wesker Mode. In this mode, Rebecca wears a rather fetching futuristic leather suit (with thigh-highs, natch) and has glowing red eyes, and Billy has been replaced by recurring series villain Albert Wesker — although all the in-engine cutscenes still use Billy’s voice, and prerendered video sequences still show Billy’s model too.

Once you take control of Wesker, you have several new abilities: a “shadow dash” that allows you to quickly get around, and a “Death Stare” ranged attack that can be devastating if used correctly. It’s an inherently silly mode intended purely for a bit of fun, but in the same way that Silent Hill 3’s delightful “Heather Beam” mode provided a surprisingly enjoyable gameplay experience in its own right, playing through the whole game in Wesker Mode feels like a good means of getting “revenge” on certain aspects of the game that maybe gave you a bit of trouble on your first run.

This is something of a running pattern for classic survival horror games in general and early-era Resident Evil specifically: they acknowledge that they’re short, and even revel in this fact by offering you rewards for beating the game quickly. In essence, the better you get at the game, the more outlandish and crazy fun it allows you to have with it, until you eventually reach a point where you’re tooled up with infinite ammo for all the best weapons in the game and can absolutely steamroller your way through every challenge that once gave you even the slightest bit of difficulty.

Alternatively, you can just finish the game, be done with it and feel like you had a satisfying experience. Resident Evil Zero certainly doesn’t feel like it needs to be any longer than the 8-12 hours I spent beating it, since in that time it takes you through some varied environments, provides just enough narrative to keep you interested in the overall series lore, sees you take on some increasingly horrifying enemies and challenges your brain with some tricky puzzles.

Clunky boss fights aside, Resident Evil Zero is still a game well worth playing today — with the added bonus that playing the new HD versions allows you to see exactly what is written on the signs in the pre-rendered backgrounds, rather than them being too blurry to read. I’ll leave the specifics of that as a fun little detail for you to discover for yourself, though…

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023