Returning to Super Mario 64 after 25 years

In celebration of March 10, Mario Day — and because it’s shortly due to be withdrawn from sale — I finally got around to picking up Super Mario 3D All-Stars recently. And despite the fact I’ve not played a lot of Super Mario Sunshine and never actually played Super Mario Galaxy, to my shame, I thought I’d start by revisiting 1996’s Super Mario 64.

Super Mario 64 is, of course, a legendary game. Is it the best 3D Mario game of all time? No, not by a long shot — its controls and camera have aged less than elegantly — but it is important.

While it wasn’t the first three-dimensional platformer — Sony’s Jumping Flash for PlayStation had it beaten by a year — it was the game that established a significant number of conventions for the genre going forward. And yet there are also a number of aspects where we can see it looking back at older styles of gameplay, too — retrospectively, this only makes Super Mario 64 more interesting to explore.

So let’s do that!

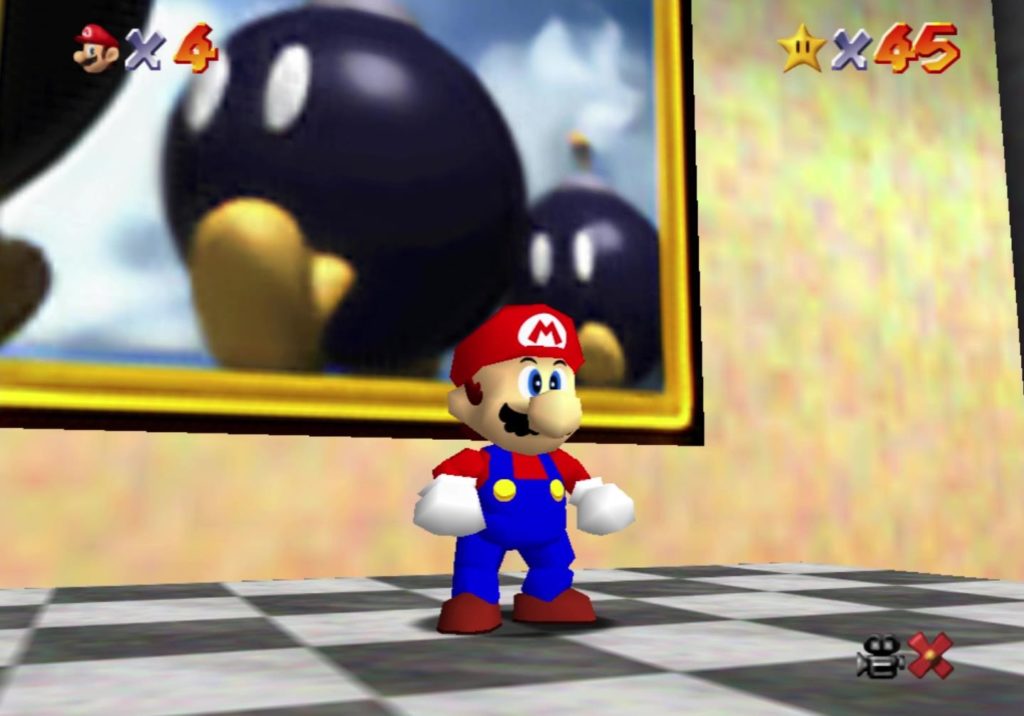

In Super Mario 64, you take on the role of Mario, of course. Mario has been invited to Princess Peach’s castle, as she has baked a cake for him. Unfortunately, on his arrival, he discovers that Peach has been imprisoned by Bowser, who has stolen the Power Stars from the castle and hidden them in a series of magic paintings. Said magic paintings act as portals to other worlds — so guess who has to jump into all of them and retrieve the Power Stars? You got it.

The very setup for Super Mario 64 provides a number of contrasts from Mario games that had come before. Perhaps most notably, this was the first time a lot of gamers had heard the name “Peach” for the Mario series’ princess; in the NES and Super NES games, she had always been named “Princess Toadstool”. She was actually first referred to as “Peach” in the west in 1993’s Super Scope game for Super NES, Yoshi’s Safari, but owing to the small install base of that peripheral and the game’s general lack of popularity, the name never really caught on until Super Mario 64.

Why Peach, though? Well, because in Japan she’d actually always been called Princess Peach — or more accurately ピーチ姫 (Piichi-hime) — and had, for some reason, been localised to Princess Toadstool for Nintendo’s early North American and European releases. Super Mario 64 actually acknowledges this with its opening letter, which Peach has signed “Princess Toadstool – Peach”. This would turn out to be a significant moment for the character’s history, as from hereon, she would only ever be known as Peach in both the east and west.

This wasn’t the only first in Super Mario 64. This was also the first mainline Super Mario game in which Mario had a “Power” meter rather than his health being determined by his size. In fact, if you want to get technical about it, this was the first Super Mario game in which Mario could not actually become Super Mario by collecting a mushroom. On top of that, he had an “attack” button — what was the world coming to when everyone’s favourite plumber was punching and kicking like a common street thug?

Joking aside, the other significant factor to Super Mario 64’s setup is that it was the first mainline Mario game where the objective was not just to clear levels, but to actually collect something — in this case, Power Stars. Super Mario World on Super NES was already inching towards this structure with the fact it counted the number of level exits you’d found on your save file, but Super Mario 64 was the first in the series to actually require you to grab a specific item to conclude a stage.

The Mario series as a whole has gone back and forth on whether or not you need to collect things in order to progress over time; generally speaking, the mainline 3D Mario titles such as Super Mario Sunshine, Super Mario Galaxy and Super Mario Odyssey have all seen Mario collecting some sort of MacGuffin to track his progress, while games that are structured more similarly to the 8- and 16-bit Mario games such as the New Super Mario Bros. games tend to simply go level by level.

The arguable exceptions to this are Super Mario 3D Land and Super Mario 3D World, but one could argue those are a distinct experience from the more free-roaming 3D Mario titles.

And “free-roaming” is a great descriptor for Super Mario 64 — it was the main aspect that distinguished itself from Mario games that had come before. Rather than progressing through a series of relatively linear levels with clear start points and finish lines, in Super Mario 64, each stage throws you into a small but intricately crafted virtual world and tasks you with exploring.

By presenting you with a vague text clue before the stage begins, you’re then expected to investigate the stage thoroughly in order to figure out exactly what that clue is referring to — and then to overcome the challenge that is inevitably waiting for you once you find the correct locations. These challenges vary enormously over the course of the game; sometimes you’ll be battling bosses, while at others you’ll be solving puzzles, using your skills of observation to uncover hidden areas or testing your dexterity.

One of the biggest joys of Super Mario 64 is coming across a Power Star “out of order”; by being particularly thorough with your exploration, it is indeed possible to find certain Power Stars before the game “intends” you to, and this is always a satisfying moment.

This is something that Super Mario Odyssey in particular built on with its Power Moons; in that game, most Power Moons didn’t bring the level to a close, but instead rewarded you for investigating the environment thoroughly, and seeking answers to the question “I wonder if I can…?” The answer, usually, is “yes” — and there’s typically a Power Moon waiting for you as confirmation.

But Super Mario 64 encourages this kind of exploration, too; the fact that each stage contains a seventh Power Star that is dependent on you collecting a hundred coins requires you to know the level inside-out and determine the best places to gather the shinies you need. Most levels contain more than a hundred coins, but in some cases not by much, so you’ll need to visit every nook and cranny in order to fill Mario’s pockets to capacity.

Probably the trickiest part of Super Mario 64 to go back to after all these years is the camera — but the important thing to remember about this game is that this was a time when a lot of developers were still figuring out exactly what the concept of a “camera” in a 3D game meant.

Prior to this point, we’d had fixed camera angles in titles like Alone in the Dark and Resident Evil (the latter of which came out the same year as Super Mario 64); we’d had first-person cameras since the 8-bit home computer era; we’d had strict behind-the-character third-person cameras in a variety of games featuring both vehicles and human characters. And no-one had yet agreed on what the “best” approach was — because there wasn’t really one single “best” approach; it all depended on the context.

With that in mind, Super Mario 64’s camera does a bit of everything at various points, and justifies this to the player by actually personifying the camera as one of the Mario series’ Lakitu characters following his adventures. This also attempts to justify the limitations on the camera at various points in the game; if Lakitu can’t get to a particular place, then you can’t put the camera there. This can, at times, be frustrating — particularly if you’re used to the freedom of camera control most games afford us with that dear old hard-working right analogue stick.

The interesting thing about Super Mario 64’s camera from a modern perspective is that there’s obviously a certain amount of “direction” going on, rather than it just blindly following a simple set of rules. There are numerous points in the game where it very deliberately frames the action in a particular way — and this is one area where we can see Super Mario 64 acknowledging and drawing from what came before as much as it is looking towards the future.

Specifically, there are quite a few points in Super Mario 64 where it almost feels like you’re playing an isometric-perspective game on an 8- or 16-bit platform — the “Filmation” games by Rare’s precursor Ultimate Play the Game are a great example. These games were typically built of “blocks” and placed clearly defined limits on the main character’s movement — normally, they could only move in the four cardinal directions, for example, and their jumping ability, if they had one, would typically allow them to clear a width of one block while moving forwards, or get high enough to get on top of a block if jumping vertically.

Super Mario 64 isn’t as restrictive in terms of movement as those old games due to its analogue controls, but you can still see certain elements of the structure and design being present. There are quite a few points where you can literally see the blocks from which the level is constructed, for example, and Mario’s different types of jump allow you to get to various locations by understanding their clearly defined capabilities. His regular jump will get him on top of one block, for example, while a backflip allows him to ascend two blocks at once if positioned correctly.

The genius of Super Mario 64’s design, though, is in the fact that it doesn’t exclusively rely on sequences like this. Contrast levels like the initial Bob-Omb Battlefield with Lethal Lava Land, for example, and you’ll see two very different approaches to 3D platforming. Bob-Omb Battlefield is open, exploratory and not all that “platformy”; Lethal Lava Land, meanwhile, is a severely punishing level, where failing to understand the quasi-isometric perspective and judging your jumps poorly can have severe consequences!

That brings up another interesting thing about Super Mario 64 — the fact that it is not afraid to punish the player, and is downright fiendishly difficult at times. While playing the game, I was struck by how frequently I felt genuine frustration at my own incompetence and a desire to yell obscenities — because a lot of modern games simply don’t provoke this reaction.

In many cases, this is a side-effect of modern games’ astronomical budgets and production values; developers want to make sure that you see everything they spent all that money on, so they make the game easier and/or more accessible to ensure that happens. Back in Super Mario 64’s day, though, if you wanted to see the game through to its conclusion, you’d better be ready to show your skills, because otherwise you simply weren’t going any further — you’d hit a wall, with no means of proceeding past it until you improved.

That said, it’s actually fairly rare to find your progress completely stymied in Super Mario 64; there are usually multiple stages you can access at any given time, so if you’re having difficulty with one, you can always go and try another one. There’s also no need to acquire all 120 of the Power Stars in the game to beat the whole thing — you only need 70 to clear the story — so if you’re happy just playing until you roll credits, you’ll have definitely still had a meaningful experience from the game as a whole.

But by the time you’ve got 70 Power Stars, you’re probably already invested in what Super Mario 64 has to offer… and so you might as well go for the full 120, right?

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023