The best reasons to play the original Shantae

WayForward’s Shantae series is pretty well-established as a range of modern classics these days — with the latest installment even having a beautiful intro by anime studio Trigger — but it wasn’t always that way.

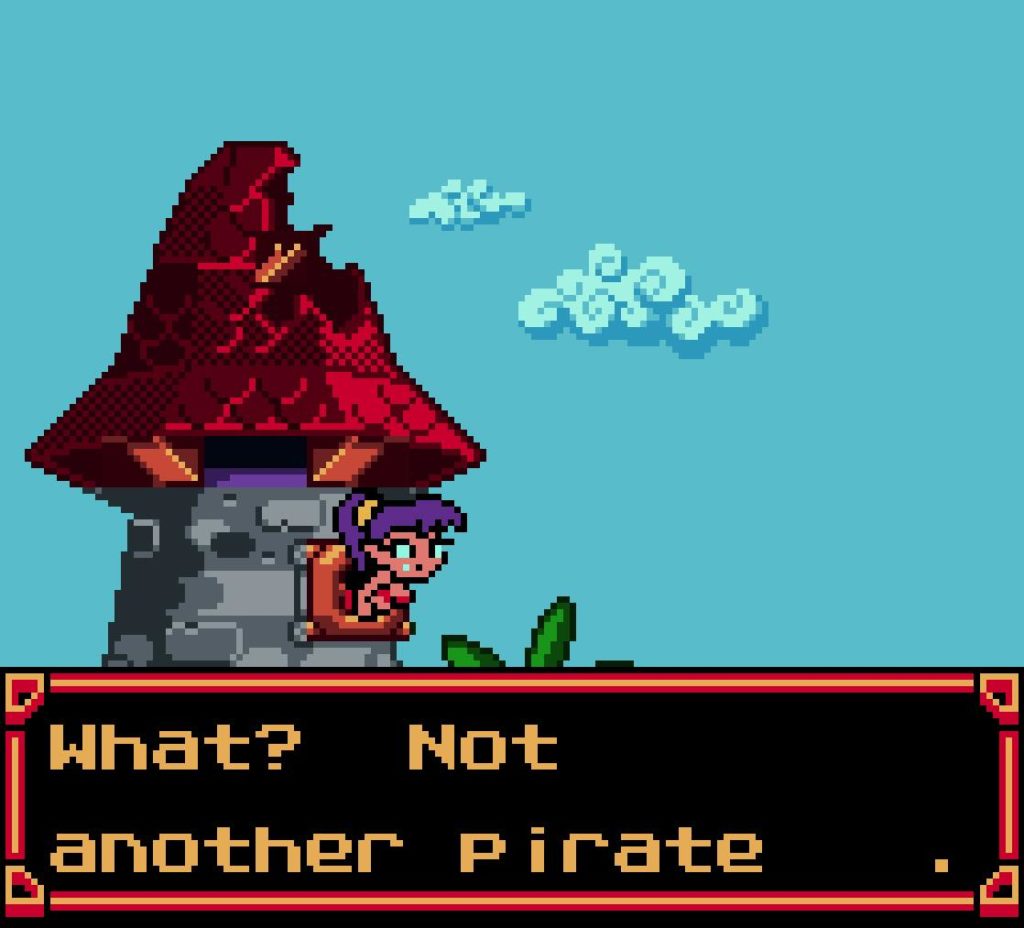

In fact, the series’ first two games passed by relatively unknown upon their initial release, with the original Shantae coming out on Game Boy Colour well after the Game Boy Advance had been released — and the second game, Risky’s Revenge, originating as a download-only DSiWare game.

After many years of being extremely hard to find in physical form — even reproduction carts will often set you back three figures — the original Shantae is returning to us via the Nintendo Switch eShop on April 22, 2021, as confirmed by WayForward themselves.

It was previously available as a downloadable title for the Nintendo 3DS, but this new release is noteworthy for a few reasons: firstly, you’ll be able to play the game on your big TV rather than being confined to a handheld; secondly, this version allows you to switch between the Game Boy Colour mode and the slightly enhanced version that unlocked if you played the game on the backwards-compatible Game Boy Advance; and thirdly, if you got in early enough, there was a physical release via Limited Run Games.

The latter is especially important to this game’s legacy; it marks the first time people will have been able to have a copy of the original Shantae on their shelf in a very long time, particularly as the Game Boy Colour original only sold somewhere in the region of 25,000 copies.

And while preorders for the Limited Run version closed in October of 2020, it’s likely that even reseller prices will be more affordable and practical than attempting to track down an authentic, working copy of the original — let alone finding it packaged.

But why should you care? Is a 2002 Game Boy Colour release really worth playing nearly twenty years later? Well, the short answer, as you’ve probably surmised, is “yes” — otherwise this article wouldn’t exist — but as for the specific reasons? Well, read on.

WayForward was founded in 1990, and initially worked on a variety of licensed video game properties on many different platforms — including some specialist ones such as the educational Leapster system. The team was hungry to work on some “proper” games for the mainstream audience, though, and started to step up their efforts in this regard in about 1997 — with Shantae being one of the first projects that the team was designing.

Legend has it that Shantae herself came about after director Matt Bozon’s wife Erin met someone while working as a camp counsellor and found herself inspired to design a character. Rather taken with Erin’s design, Matt decided to build a game based for this new character, though the initial concept for what would become the original Shantae was rather different to what we ended up with!

The original plan for the game was to create a three-dimensional game for PlayStation and PC, featuring prerendered backdrops with traditionally animated characters atop them moving in 3D space. The design documents from the period describe it as being “the long-awaited blend of 2D’s fluid animation and 3D’s next-generation gameplay rolled into one!”

While the eventual end product abandoned a lot of the ambition from this original design document, it kept a lot of structural elements — most notably, the fact that the game’s world would be designed in a “ring” format, allowing you to wrap all the way around from one end to the other, and that throughout the world there would be both towns and monster lairs to explore.

The eventual decision to run with the Game Boy Colour as the platform of choice was, according to Matt Bozon, a case of the team at WayForward realising that “a small team [could] focus on making a good game and be relatively left alone; it allows for more creative freedom and flexibility of design, which ultimately leads to a better game.” This is something that WayForward has stuck to over the years; while their games, on the whole, have a lot more recognition than they once did, they’re still developed using this fiercely independent mentality, and it has had a consistently positive effect on their output over the years.

Part of the decision-making process also likely involved the fact that WayForward had already been working on a number of other Game Boy Colour titles around the same period — with the most notable including two games based on the animated spin-off series for Sabrina the Teenage Witch, and a Casper the Friendly Ghost spinoff called Wendy: Every Witch Way.

Interestingly, while Shantae became the most well-known title from WayForward’s Game Boy Colour output, all three of these games run on the same impressively slick 2D engine that powers Shantae, so if you particularly enjoy our half-genie heroine’s first adventure, you may want to seek out copies of these lesser-known licensed titles, too; they’re genuinely good.

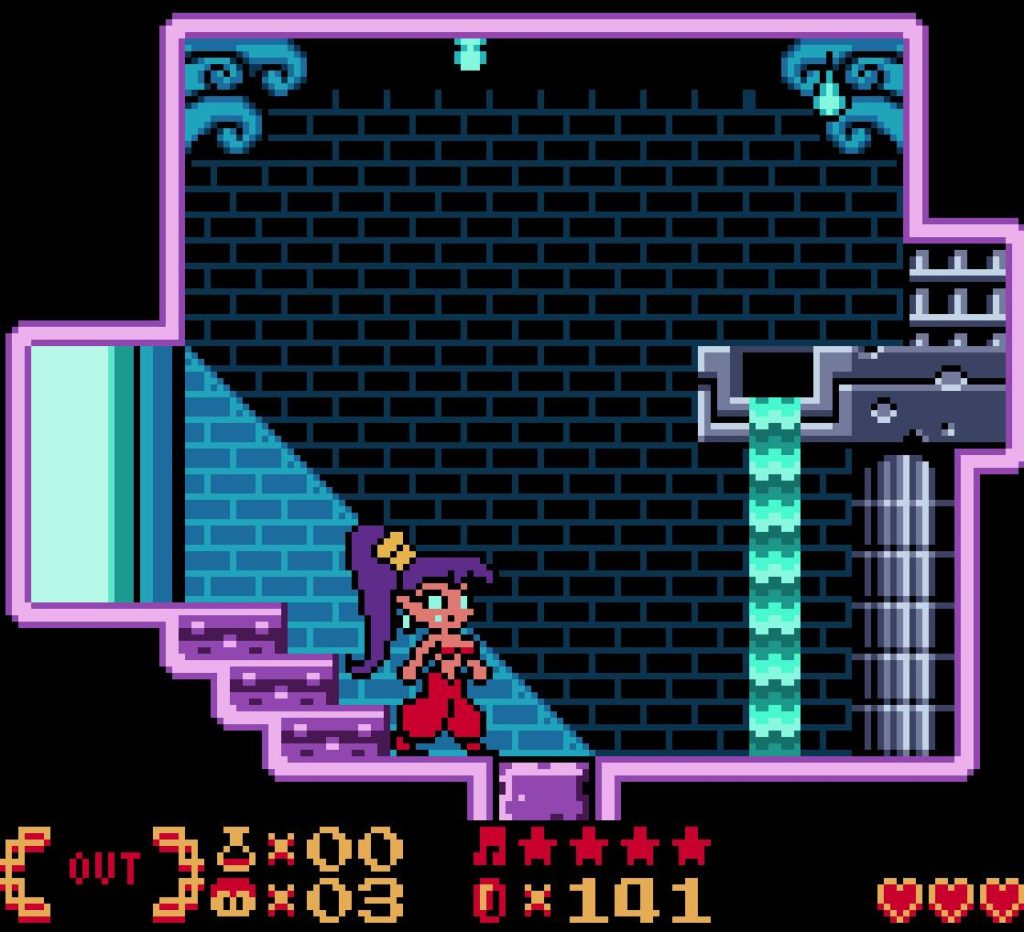

Shantae is an open-structure side-scrolling 2D platform game in which you explore a world, make your way into dungeons, defeat bosses and obtain new powers for our heroine. There are elements of Zelda, Metroid and Castlevania in there for sure, but Shantae manages to be much more than just another take on those existing formulae, it does a bunch of things differently.

Perhaps most notable is that in contrast to many other open-structure 2D platformers, the various areas through which you proceed aren’t small, screen-sized areas; instead, each region of Shantae’s Sequin Land setting is roughly the size of what we’d consider to be a “level” in a more linearly structured platformer. Not only that, but you’re forced back to the start of an area if you die while proceeding through it — and Shantae has a limited number of lives, sending you back to where you last saved if you run out of them.

While these may sound like outdated gaming conventions, they add a sense of challenge to Shantae, and make traversing the world feel like there’s a genuine sense of danger to it. And there are some nods to “modernity”, too — despite being sent back to the geographical location of your last save point upon continuing, the state of the world and dungeons does not reset to how it was when you last saved, meaning any puzzles you’ve solved along the way remain solved. This strikes a good balance between providing you with a mild punishment for messing up without simply forcing you to grind through the same activities again.

Another interesting design choice in Shantae is the fact that there’s no in-game map, either out in the overworld or in the dungeons themselves. This is entirely deliberate, as out in the open it means you’ll have to navigate by landmarks — and there are plenty of them — while in the dungeons you’ll find there’s a natural sense of progression, despite the fact that the layouts might initially feel quite “open”.

Shantae also makes a point of not giving you explicit instructions throughout the game; you might be given some vague directions as to the direction your next objective lies in — though on one occasion you’re actually told to head the wrong way — but otherwise the game encourages you to experiment, spot background details and work out exactly what the on-screen feedback you’re getting actually means.

Good examples include one dungeon where Shantae has the ability to swap colours between blue and red, with enemies and environmental elements interacting with her in different ways according to her current colour; and another dungeon where your main task is hair-whipping stone eyes into statues in order to create amusing scenes such as said statue ogling a large-breasted genie statue. The game never tells you exactly what you’re supposed to do in these situations; it expects you to ask the question “I wonder if…” and then try to find an answer for yourself.

And besides all these interesting design, structure and mechanical choices, the game is still absolutely wonderful to look at and listen to. Every sprite in the game is beautifully animated and works well within the inherent limitations of the Game Boy Colour’s technical specifications. Jake Kaufman’s fantastic soundtrack pushes the poor old Game Boy Colour’s sound chip to its limits And the whole thing has aged beautifully; with the distinctive Game Boy Colour look starting to come into vogue with indie developers, it’s the perfect time to revisit Shantae, a game that demonstrated absolute complete and utter mastery over the platform.

Shantae is a fantastic game, and it’s a delight to finally see it get the recognition it deserves. I hope you’ll all join me in revisiting its brilliance when April 22 rolls around.

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023