Why we can never get enough of The Wallflower

The Wallflower (or Yamato Nadeshiko Shichi Henge – “Perfect Girl Evolution”) originated as a manga written and illustrated by Tomoko Hayakawa, and is regarded as her pièce de résistance.

It feels remarkably similar to Paradise Kiss many ways, right down to them both being untraditional shoujo manga. The two having a solid emphasis on representing and exploring fantastic fashion; it’s all to provide us with some visual stimulation, but it’s also important to the characters. There’s so much more to it, and arguably more so with The Wallflower.

The Wallflower spawned not only an anime adaptation that was enjoyable in its own right, but also a live-action adaptation that rivals its own source material – which most definitely beats Paradise Kiss’ live-action movie.

I’ve held off discussing The Wallflower for quite some time, simply because I felt that I wouldn’t do it justice. But at the same time, I also feel it’s nowhere near as highly regarded as it deserves to be — and the way in which it goes against the grain is remarkable and impressive. The result is an impactful series that sets up a variety of wise, life-changing moments in a package that bucks the trends of most other shoujo manga out there.

Allow me to explain!

The Wallflower pulls no punches

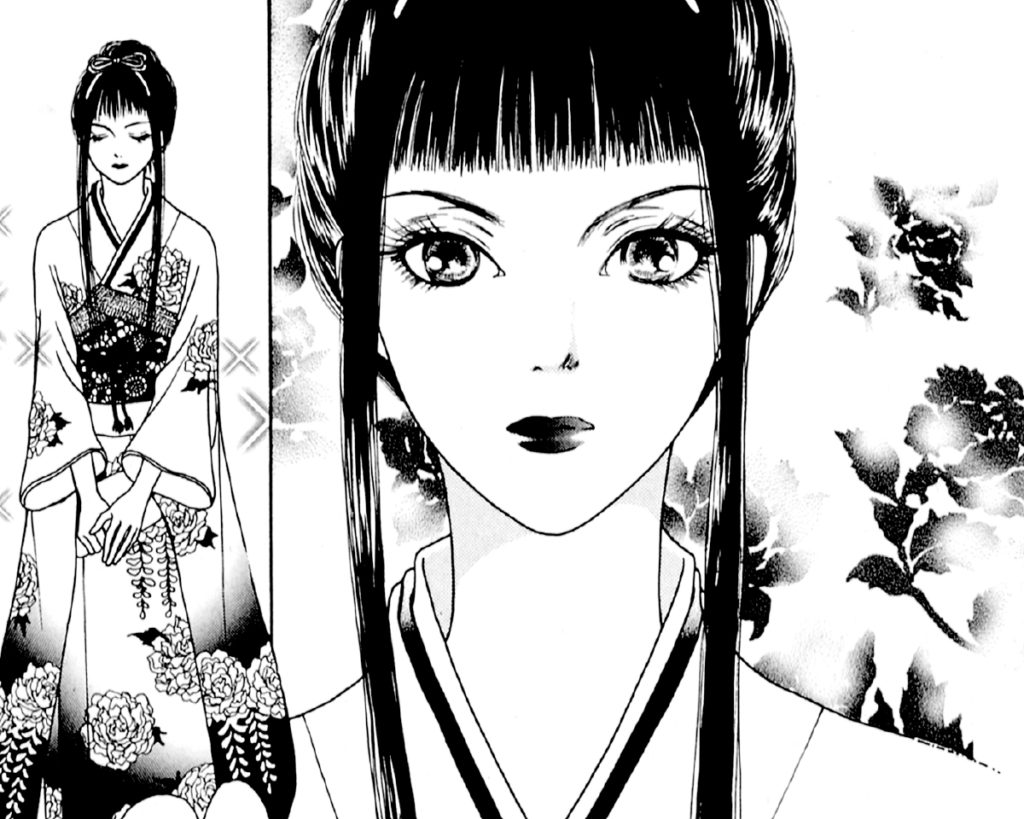

The Wallflower originally ran from 2000 to 2015; it took a Gothic punk motif and a shoujo structure, and applies them to a modernised My Fair Lady-style storyline. Its main character, Sunako Nakahara, is a teenager who once professed her love to her crush in middle school, but his response was “I hate ugly girls”.

Unsurprisingly, Sunako plummets in self-confidence as a result. She ends up hiding her face behind her long, black bangs, giving her a Sadako of The Ring vibe; she talks almost exclusively to her skeleton model companions; she has a phobia of attractive people; she’s pretty much a hermit; she continuously puts herself down; and has no drive to change herself.

Meanwhile, the other characters are specifically tasked with trying to change her. Sunako’s aunt implores four young men, who currently live in her establishment, can remain there rent-free if they can make Sunako into a proper, elegant lady. But if they fail, they will owe triple the normal rent.

The four boys are of varied attitudes and temperaments, as you might expect for a reverse harem. There are some parallels that can be drawn between them when their backgrounds are explored in more depth, but they can all initially be summed up in a word or so.

There is the playboy Ranmaru; the intelligent and stoic Takenaga; the childish youngster Yukinojo (Yuki for short); and its main boy, Kyohei, the brutish and mouthy one, who has the biggest risk riding on the deal since he is unable to hold down a job. The stakes are highest with Kyohei not just because of his living situation, but also because of a prevailing sense of “will they or won’t they?” with regard to his relationship with Sunako.

The progression of The Wallflower’s story is almost completely episodic. It feels like it’s following a template more often than not, with much of the slapstick and comedy deriving from Sunako’s unusual behaviour. It plays out very much like the very best otome romcoms, with the suitors having to learn to accept Sunako for who she is, while each one of them have their own clashing personalities and conflicting interests. They all need to learn from one another in order to understand each other better; a real sense of self-improvement comes from how they end up building one another up.

The result is a slow-burn of a plot with realistic character development over a natural-feeling course of time. We learn to love all of The Wallflower’s characters for all their faults and gradual self-improvement. And what initially appears to be a reverse harem premise is also subverted, since the boys aren’t competing for Sunako. They sure have a slowly growing sense of camaraderie between them, but this is due to them having to overcome their seeming incompatibility with one another.

A punk motif, and atypical shoujo progression

Kyohei has a Sylvain from Fire Emblem: Three Houses deal going on to explain his motivations: women only pay attention to him for his appearance and look no deeper into him; it’s pure shallowness.

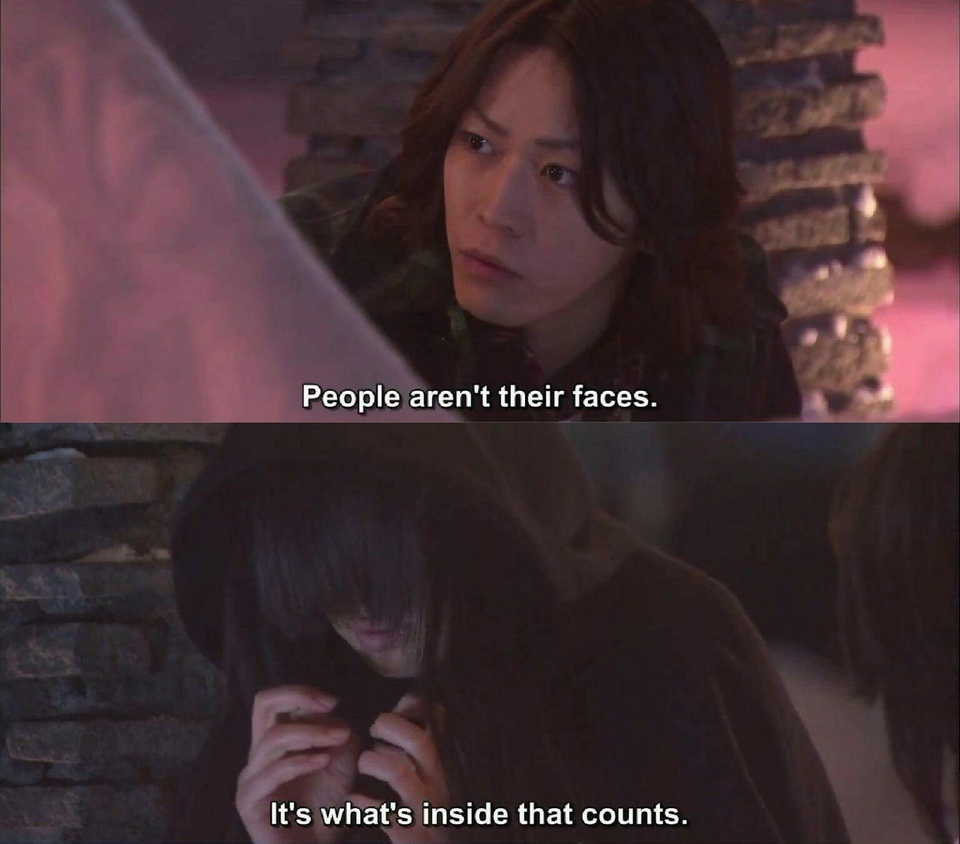

He is kidnapped too many times to count during the series because of his sheer beauty, and his trauma is derived from him being carved by the Gods, something that has him keep everyone at arm’s length. He feels both familial and romantic pain as a result of others disregarding his feelings and wellbeing. His character lays the groundwork for The Wallflower’s major themes of not judging a book by its cover, and how beauty can actually be a curse.

In fact, The Wallflower’s characters all have varied issues that will be relatable to certain audience members. The main “harem” group are a lot more sympathetic and human than one might expect, and this is, of course, a major part of the series’ prevailing message of not taking people at face value.

Yuki is considered the baby of the group, having quite an androgynous appearance which is played up when he cross-dresses, but his childish attitude hides the sense of inferiority and incapability he grapples with when comparing himself to others. He also will arguably be the most relatable to the general audience member, since he comes from a rather humble, working-class background.

Takenaga makes for an interesting contrast to how Sunako and Kyohei are constantly at each other’s throats. He is the first to successfully approach Sunako and acts the most civil with her, and we learn that this is likely down to their parallel pasts. His stoic and well-guarded nature hides the difficulty he has with his family, whose high expectations of him made him as reserved and quiet as he is.

Then we have Ranmaru, who is the biggest silver-spooned boy of the lot. He was plopped into the mansion of his own parents’ volition after all. His arrogance and inability to do things for himself causes him to have a bit of a reality check when attempting to form bonds with the other guys. He ultimately learns to see the value in rethinking his attitude after his change in living conditions and arranged marriage.

Sunako herself is the easiest to identify with when it comes to the issues she struggles with, since she is the focal point of the series. There are so many aspects worth noting here, but possibly the most well-intentioned and satisfying is the depiction of she sees her own body image.

She is visually shown almost always in a chibi form to reinforce her own stunted view of herself. She also happens to be the main source of eccentricity within the cast — and this is likely something that runs in the family, considering her aunt’s knack for appearing both on- and off-screen in the most wild and grandest of fashions.

Sunako is a nutcase in the best way possible, with her love for the darkest of comedies always becoming an issue for the cast, and providing the bulk of the humour for the audience — even if it’s as extreme as her threatening to seriously kill beautiful people (or, rather, Kyohei).

In fact, The Wallflower is primarily a dark comedy with romantic plotlines on the side, and the comedy is as dark as the genre goes. It is very juvenile, with crude humour that even tries to play up scenarios involving contemplating suicide, and even attempted rape, which are the only tone-deaf moments of the product in question. It’s unquestionably eccentric, and despite all the complaints from over the years about its art style, humour and slow character progression, at its very core, its heartfelt messages remain important to anyone who feels critical of themselves and fails to see their own worth.

Because no matter when you come to experience The Wallflower, or how old or forgotten it may be, what it has to say is straight to the point and as authentic as it comes.

The prevailing message of being your true self is deserving of love

The manga originally drew criticism for how seemingly lacking its character development is, but that’s exactly where the series shines: its subtlety. Sunako gradually changes bit by bit, but even then, she stays true to herself and never fully accepts becoming the “Fair Lady” even in the end.

Everyone learns to accept themselves, because that is the main lesson to be learned and taken from the series’ teachings. Whilst Sunako does indeed develop, the attributes that make her so unusual and unique are exactly why Kyohei falls for her, and these things remain defining characteristics of hers despite her progress in other areas.

Despite being more comedy than romance, The Wallflower still has plenty of relationships with their own plotlines and conflicts explored here and there that run right up until the very end. This is especially apparent in the case of Sunako and Kyohei, because they never actually do get together.

Their potential as a couple is made consistently obvious to everyone — both characters and audience — but the emphasis on their relationship is their acknowledgment of how they are each improving their own attitudes and moving their hearts enough to open up the possibility of exploring love once again.

While it does not give us the sense of closure most shoujo manga readers would otherwise expect, those who are a sucker for romance can instead enjoy the pre-existing romantic relationship between Takenaga and Noi, and the progression of an arranged set-up between Ranmaru and Tamao. Ultimately, there’s something for every romance lover here, with each stage of a relationship getting its own focus and themes — even if those relationships don’t necessarily involve the “main” cast members.

While the other characters have their own self-contained romances and plotlines, the overall focus of The Wallflower never stops being on how everyone comes to value Sunako. Platonic love is just as emphasised as romantic love in The Wallflower, and it obviously plays a massive part in developing the overarching theme of self-love.

The boys do not all stay in long-lasting romantic relationships, and it is satisfying to see, because their characters’ ultimately find closure and comfort from the friendships that they made as they progressed through their own personal journey.

The Wallflower’s message is clear, loud and confident, and is one that deserves continued recognition for generations to come: love yourself, even with all your own faults and weaknesses, and understand that everyone deserves to be loved in return. Find comfort in having a supportive circle, but improve yourself for the better by your own volition rather than feeling forced to do so. Nothing changes instantly, and that is exactly what growing up is all about. It’s a steady process, and no one is doing that incorrectly.

If you happen to be a newcomer to The Wallflower, then welcome! The manga is arguably the best gateway in — you can grab it via Amazon, but note that there are 36 volumes in total!

If you want a taster of what it is about, meanwhile, the 10-episode live action adaptation is just as good of a starting point. I’d recommend it over the anime for a much better balance between comedy and heartfelt moments. It also includes a character who is exclusive to the live-action adaptation: Takeru Nakahara, the brother of Sunako, and he provides some really well-implemented points of further characterisation and development between the cast.

However you choose to experience it, The Wallflower is an excellent series worthy of your time and attention. I can’t get enough of it — and if you let yourself get drawn in, I suspect you won’t be able to either.

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Sigh of the Abyss: Shadow Bonds – Prologue Review - October 7, 2023

- Is She The Wolf? is wickedly addicting TV - October 6, 2023

- The steady consumption of Slow Damage - October 5, 2023