Virtue’s Last Reward: when mechanics become narrative elements

One of the reasons that Kotaro Uchikoshi is so well-liked as an auteur of the video game medium is that he is not attempting to mash together two disparate forms of media into a story-centric video game; rather, he fully embraces the “video game-ness” of his work while, at the same time, emphasising the narrative components.

The second Zero Escape title, Virtue’s Last Reward, is one of the best examples of this — but we’ve seen plenty of it in the other Uchikoshi games we’ve explored in this feature so far, too.

For example, World’s End Club features diverging narrative paths which must be experienced in their entirety in order to unlock the game’s real ending.

The first AI: The Somnium Files game features a single story that branches off in multiple very different directions, all of which have something useful and interesting to tell the player.

Nirvana Initiative builds on this by raising interesting questions over the timeline that you, the player are perceiving.

And 999 not only has some “bad” endings as prerequisites for its “true” conclusion, said finale does some very interesting things with the roles of the player, the narrator and some of the participant characters.

Virtue’s Last Reward takes things to a whole other level, though. And to talk about what makes it so interesting is inevitably to spoil some of it — so consider this the one and only spoiler warning that you will get in this article.

The initial setup for Virtue’s Last Reward is similar to 999, the first Zero Escape game. A series of nine disparate individuals have found themselves trapped in an enclosed environment, and are forced to play a game that will kill them if they don’t follow the rules.

Said rules are a little different this time around, however. Rather than simply exploring their surroundings and proceeding through numbered doors, the participants are sorted into colour groups which determine which “Chromatic Doors” they can proceed through, and after locating special key cards in the series’ iconic puzzle rooms, they are able to play the “Ambidex Game” or “AB Game”.

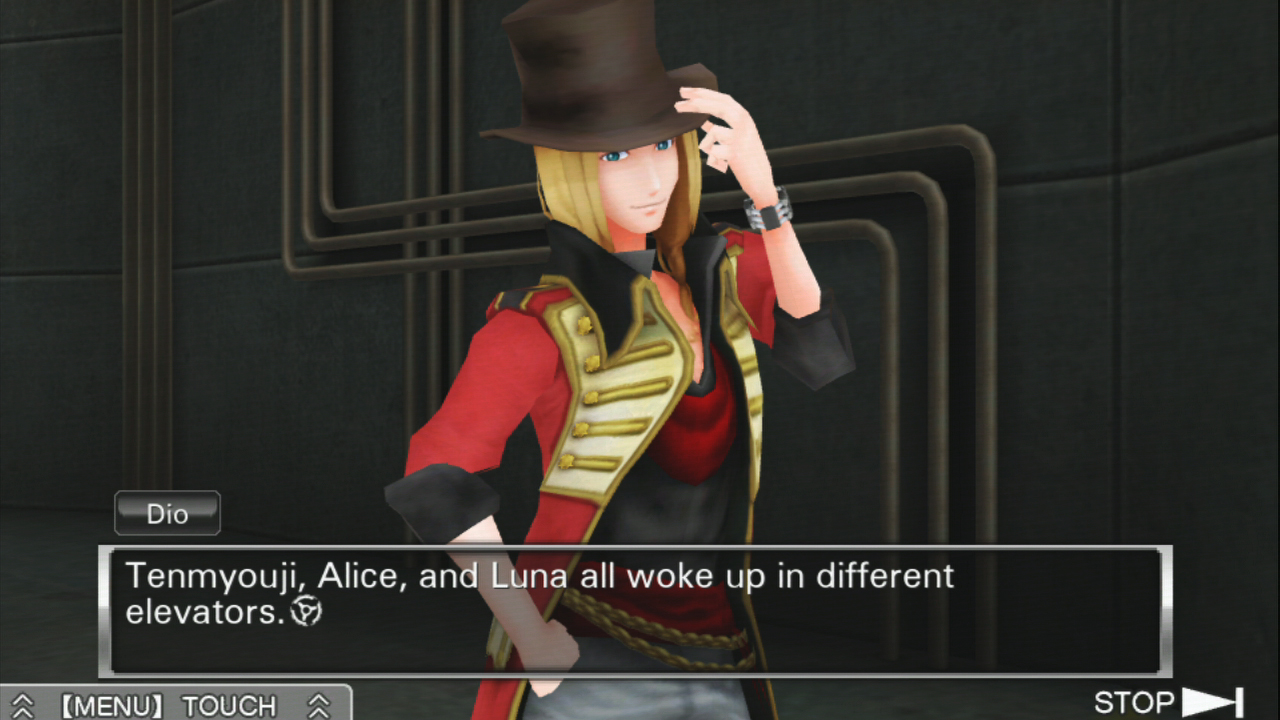

This is a take on the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma scenario. The three members of a colour group — two who act together as a pair, and one who acts alone — are shut in a room for 45 minutes and asked if they want to Ally with or Betray their counterparts. If both ally, they get two points each. If both betray, no-one gets any points. But if one betrays and the other allies, the betrayer receives three points while the unwanted ally loses two points. Attain nine points and it becomes possible to open the exit door; drop below zero points and you are killed.

The first thing you see during Virtue’s Last Reward’s introduction sequence is the question “Why do people betray one another?” — and this is a fair question to ask. Given that several characters point out at the beginning of proceedings that all everyone needs to do is vote “Ally” every time for several rounds of the AB game and everyone will be able to escape, it can be difficult to understand why anyone would choose “Betray”.

But that’s human nature. Humans don’t necessarily always work together for the greater good, and sometimes focus on selfishness. If someone can provide themselves an advantage, with the cost being a disadvantage to someone they don’t really know, then there’s a fair few people on this Earth who will take that advantage without a second thought. Thankfully, there are also plenty of people who would reject the possibility of putting someone — even a stranger — at a disadvantage in the name of their own selfish goals.

This is one of the things that is particularly interesting about Virtue’s Last Reward. Out of the nine characters, none of them are particularly clean-cut examples of being “good” or “evil”. One in particular is obviously suspicious from the outset — and doesn’t do much to dissuade us from that opinion over the course of the entire game — but there are also others who, in several of the routes through the game, make some very surprising choices.

It’s a fair assumption to say that in Virtue’s Last Reward, if it’s possible for something to go wrong, it probably will. Characters end up dead. Mysterious happenings abound. People who seemed trustworthy turn out to be backstabbers. And in many cases, the true motivations of the people playing this strange game remain unclear.

Like in 999, Virtue’s Last Reward presents you with a few opportunities to make choices along the way, and these are what determine down which narrative paths you will proceed. There are two main types of choice you’ll be asked to make: firstly, which characters you want to see protagonist Sigma cooperate with (and, by extension, which Chromatic Doors they will proceed through) and secondly, how Sigma will vote in each round of the AB Game.

Between the main narrative beats, you’ll be asked to solve various escape room puzzles, with the exact ones you encounter being determined by the narrative path you’re on — each route features its own unique rooms to challenge, with 16 in total necessary to complete in order to beat the entire game.

On the whole, Virtue’s Last Reward’s escape rooms are more challenging than those found in 999, with some particularly tricky maths puzzles along the way. It’s helpful to have a pen and paper to hand to work things out — unlike 999, Virtue’s Last Reward doesn’t feature an in-game calculator, and the in-game “Memo” function, which was originally implemented as a touchscreen control on the game’s original 3DS and Vita releases, doesn’t work great with controllers.

An interesting addition to the formula is the fact that each room has two “solutions”, with each providing a code for the room’s safe. The first unlocks the door and provides a variety of story-critical items, while the other provides access to a special file that gives the player (and specifically the player, not the characters) some background reading material on the situation. How “complete” the file is depends on if you are playing on the default “Hard” difficulty, or if you drop it down to “Easy”, where characters will offer increasingly obvious clues to help solve the puzzles if you’re really struggling.

These secret files already place the player in an advantageous position compared to the participant characters in the game, but things go a little further than that in Virtue’s Last Reward. There are several narrative sequences that conclude with a “lock”, which indicates a seemingly hopeless situation from which there is no escape. These locks can be resolved by discovering information in other narrative routes, then bringing that information back to the original situation and using it to your advantage.

This idea is standard practice for visual novels to a certain extent — most multi-route games demand that you play all characters’ routes in order to get a full understanding of events, even where those routes might seemingly contradict one another. Where Virtue’s Last Reward is a bit different is in the fact that some of the characters are aware of this — specifically, protagonist Sigma and his initial partner in the narrative, a girl named Phi.

To begin with, this idea is initially teased simply as characters “knowing things that they shouldn’t” — a trope that was also used in 999 with the way its endings interacted with one another. But as Virtue’s Last Reward progresses, it becomes increasingly apparent that when you, the player, “jump” back to a particular node on the game’s story flow chart, you’re actually bringing Sigma’s consciousness along for the ride, too. The further in the game you go, the more noticeable this becomes — with some sequences even featuring unique narration and dialogue depending on which order you complete them in.

Ultimately, “solving” Virtue’s Last Reward becomes a matter of untangling these many different possible timelines and using the information from each in order to reach some sort of conclusion. And this isn’t a process that just happens automatically, either; on several narrative routes you’ll be asked to manually input things that you and Sigma have heard in the other routes. While it’s easy to jump back to the relevant scenes and recover the information if you’ve forgotten it, it’s generally a good idea to write anything down that sounds like it might be important, because it probably is.

You’ll notice that outside of the “jumping” aspect, we haven’t talked much about the specifics of the narrative in Virtue’s Last Reward today. And that’s entirely deliberate; this is one of those games where going in as blind as possible makes it far more interesting, particularly if you’re coming straight from 999. You will doubtless come to suspect things about certain characters in the game well before you learn the truth about them — and that sense of “not knowing for sure” is one of the best things about Virtue’s Last Reward.

As you might expect, the idea of jumping one’s consciousness through time and reliving events with different possible outcomes does get a little convoluted by the end of proceedings — but it does make consistent internal sense according to the logic established by the story. It also sets up the next game, Zero Time Dilemma, very nicely indeed — though interestingly at the time Virtue’s Last Reward was originally released, a third and final installment in the Zero Escape series looked like it might not happen.

This would have been a crying shame, as while Virtue’s Last Reward goes on for 40+ hours, both asking and answering a lot of interesting questions along the way, its conclusion also sets up a brand new scenario that, in another timeline, we might never have seen a resolution to.

Opinions are divided on whether or not Zero Time Dilemma actually was a suitable resolution to the series as a whole, mind you — but that’s a story for another day.

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023