Video game collecting has never been better… or worse

Chances are, many of you reading this are avid collectors of some description. There is a significant crossover between fandoms of things that are considered “niche interest” and those who enjoy outwardly showing tangible signs of their passions, after all.

Video game collecting has been a thing for many years at this point — even long before the rise of the Internet, people were trying to collect complete sets of Atari 2600 cartridges, or all of the RPGs on PS1, or every commercially released cartridge for the N64, that sort of thing. But with the rise of social media, video sharing sites and other means of collectively enthusing about one’s hobbies, this side of things has exploded in recent years.

It is an amazing time to be interested in video game collecting. But it is also a terrible time to be interested in video game collecting. It’s ultimately up to you as to whether the good outweighs the bad — or vice versa!

The bad side of modern video game collecting

Let’s get this side of things out of the way first so we can get on to the happy enthusing — because there are a number of important considerations with regard to video game collecting that are worth bearing in mind before you decide to jump into the hobby wholeheartedly. And those considerations vary according to what era of gaming you’re interested in collecting.

If you’re an old-school gamer interested in video game collecting, the unfortunate truth is that as the physical products which contain the games age, many of them become more prone to failure. Batteries fail in cartridges, making it impossible to save your progress; magnetic media decays and is prone to damage from dust and scratches; some forms of optical media are also starting to decay, too — and the older the disc format, the more fragile it is.

The good news is that most of these video game collecting problems have a solution. Cartridge batteries can be replaced relatively easily — or even replaced with alternative solutions if you’re feeling a bit more ambitious. Magnetic media can be backed up before it decays beyond repair — either to newer magnetic media, or alternative forms of storage. And you can even repair optical media with a bit of care and attention.

The other downside to old-school video game collecting is that pricing for older platforms and their software gradually creeps up as time goes on — particularly for the games that people particularly want to revisit. Nab a well-regarded cult classic RPG for PS1 or PS2 for less than fifty quid and you’re doing well; pay less than three figures for something like Panzer Dragoon Saga on Saturn and you’re doing brilliantly.

This is one side of things where social media and YouTube haven’t helped matters. There have been numerous cases over the years of popular (or once-popular) YouTubers talking about a game and it suddenly starting to command obscene prices on the second-hand market. The YouTubers themselves aren’t to blame for this, of course, but it’s an unfortunate side-effect of video game collecting becoming a broader hobby that more people are interested in — and something that some of the less scrupulous out there have seen as an opportunity to make some big money.

If you’re interested in collecting more “current” media, however, the considerations are entirely different. In many cases, the problems aren’t actually problems right now — but there’s the possibility they may well become serious issues in, say, 20 or 30 years’ time. While we can still put an Atari 2600 or Super NES cartridge into a console right now and, assuming the console itself is in working order, play a game exactly as it was originally intended… the same might not be true of today’s PlayStation 4, Xbox One and Nintendo Switch games.

The reason? It’s all down to Internet connectivity. From the late 360/PS3 era onwards, video game developers felt empowered to release retail versions of games that perhaps weren’t quite as good as they could be — safe in the knowledge that they could just distribute a patch online that would fix any remaining issues.

This had been a thing in the PC space for many years at this point, of course, but the difference was that retail, physical PC games — yes, they once existed — would usually ship in complete form, without the need for substantial patches. There were a few exceptions here and there, but for the most part, you bought a PC game and it worked just fine straight out of the box — perfect for video game collecting.

Another key difference is that it’s easy to back up those patches for older PC games, burn them to a CD or USB memory stick and just bung them in the box with the original media. That way, even if the patches are no longer being distributed officially, the game can still be played in its optimal form.

Today, though, we live in an age of automatic updates without warning. Pop in a disc to your PS4 or Xbox One (or a cart in your Switch) and chances are one of the first things that will happen is that a patch will be downloaded, immediately rendering that disc you bought potentially useless from a video game collecting and archival perspective.

Sometimes this is a more serious issue than others. At the one end of the spectrum, a lot of modern, low-to-mid-budget Japanese games can simply be put in the drive, get installed in a matter of seconds and be ready to play just like how the PS2 and earlier consoles worked. I can’t remember the last Compile Heart game I played that required a day-one patch, for example — though Cyberdimension Neptunia: 4 Goddesses Online did have one hell of a load time on it.

And then you have cases like Final Fantasy XV, a game which was almost unplayable in its on-disc form — though there’s a fun subsection of that game’s fandom who specifically enjoys experimenting with the unpatched version. Final Fantasy XV had numerous, multi-gigabyte updates over its lifetime that included not just bug fixes but in some cases radical new gameplay mechanics. If you played Final Fantasy XV at launch and you play it again now, you’ll likely have a markedly different experience.

Square Enix countered some of this by releasing the Royal Edition, which included both a more up to date version of Final Fantasy XV as well as the DLC that had been released up until that point — but then completely negated the point of the whole thing by announcing another episode of DLC and continued development on the game. And to date, we’re yet to see any sort of “Ultimate” or “Definitive” edition of Final Fantasy XV that just has everything on the disc.

This sort of thing, particularly on consoles, is a lot harder to fix. There are ways of backing up today’s automatically applied patches and updates on both PC and console, but they’re typically not as accessible as simply downloading an installer application and saving it to a USB stick — especially if you’re not someone who habitually mods your consoles.

This issue may not seem like a huge problem for video game collecting right now, but as soon as Sony, Microsoft, Valve or whoever else decides to pull the plug on hosting those automatically applied game patches, many of those disc copies will suddenly provide suboptimal, unrepresentative or even unplayable reflections of what the games they contain were like at their best. This is an archivist and historian’s nightmare — and it’s something that, at present, the industry as a whole isn’t doing nearly enough to prepare for.

The good side of modern video game collecting

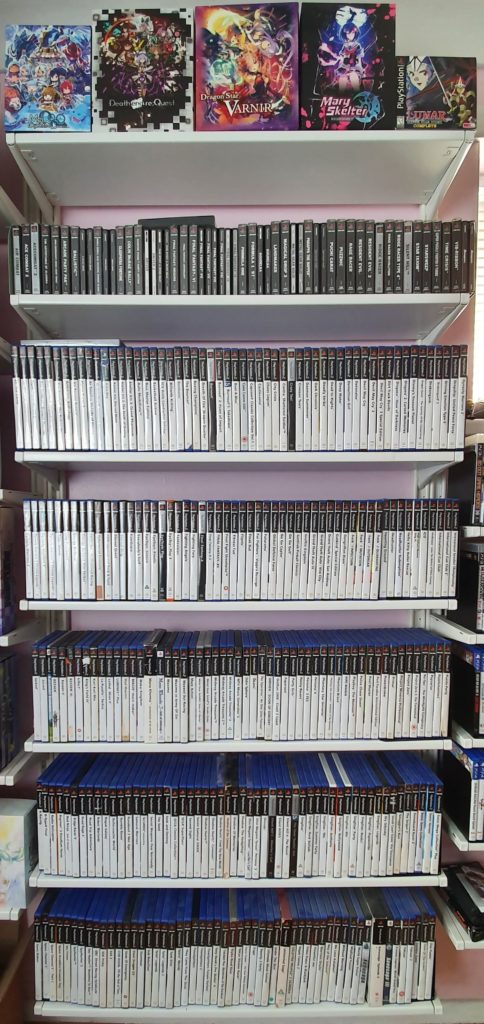

That isn’t to say no-one in the industry is doing anything about this, however, and it’s here that the numerous limited-press houses that have sprung up over the course of the last few years enter the picture. Ever since Limited Run Games set the standard for their physical releases as only appearing once the games were definitively “finished” — that means all the patches had been applied and all the DLC had been released — we’ve seen a variety of different companies dedicated to the pursuit of preservation, and of making modern video game collecting as practical as possible.

In fact, let’s give a shout-out to some specific companies, because these guys are working tirelessly to preserve a lot of games that might otherwise end up forgotten. So mad props not only to Limited Run Games, but also Super Rare Games, Strictly Limited Games, First Press Games, Premium Edition Games and many more besides.

Given the existence of these companies, if something comes out these days as a download-only game and turns out to be a big hit, you can usually count on it getting a limited physical release down the road — you just have to learn to be patient. And, given the sheer number of video games that exist in the market today, this shouldn’t be a problem for most people.

Limited Run Games in particular struggled greatly with scalpers buying up all their stock and then selling it at inflated prices on eBay in their early days, but in more recent years standardised preorder practices have been put in place to prevent this from happening as much as possible. You’ll still likely want to get in and preorder as soon as it becomes available, but thankfully for the most part we no longer live in an age where if you’re not clicking “Checkout” within thirty seconds of the product going live, you ain’t getting it.

Of course, the “limited” nature of releases from limited-press houses begs the question as to whether or not this is “true” preservation, since the number of copies out in the wild will have a hard cap rather than simply being manufactured according to demand — but given the gap between the original digital release of most games that end up as a limited-press title and their actual physical release, it’s pretty safe to rely on the fact that, for the most part, the people who are buying these limited-press versions are people who are serious about video game collecting: the ones who are keeping and treasuring copies of their favourite games.

The same goes for games from companies that specialise in niche-interest products. Take the special editions of games we sell on our own Rice Digital store, for example; these provide the opportunity for people willing to jump in “day one” to pick up beautiful physical copies of games they’ve been eagerly anticipating, whether it’s Gal*Gun Returns, Root Film, Tormented Souls or Kowloon High School Chronicle. And once they’re gone, they’re gone!

All this also raises an interesting point about the idea of “complete” collections. For past console generations, it was theoretically possible — although challenging in many cases — to obtain a “complete” collection of every available game for a console, with the Nintendo 64 typically regarded as the “easiest” of the mainstream retro platforms to achieve this on due to its relatively limited library.

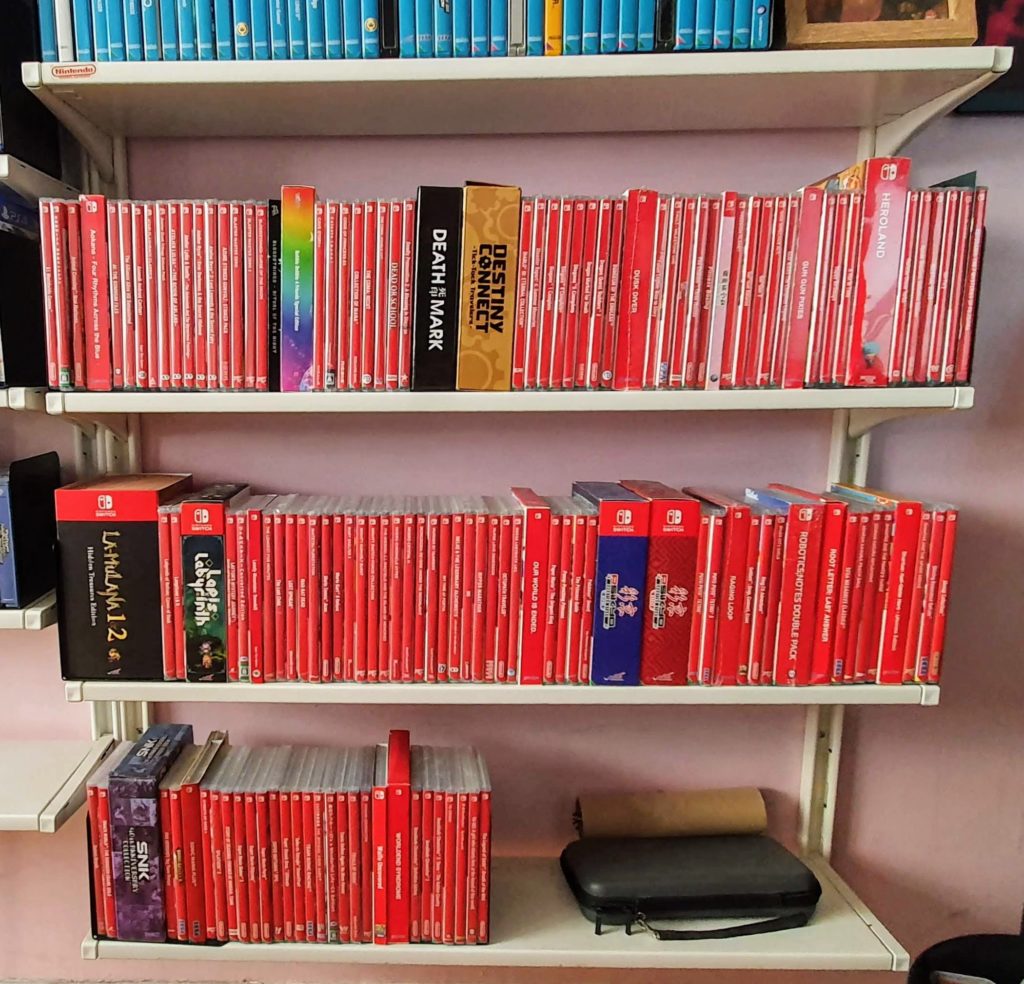

These days, however, because so many releases on modern platforms — particularly Switch — come in the form of limited-press versions, we have a significantly increased likelihood that everyone’s library is going to look a little bit different. And while that might be a bit frustrating for video game collecting completionists, for my money it makes things much more interesting. If I go to visit my friend’s house (observing good social distancing practice, obviously) and look at his Switch shelves, I know that he’s going to have a very different lineup of games to what I have. And I love that.

And limited-press companies aren’t the only way that different people’s video game collecting is likely to be wildly divergent from each another. The rise of the English-speaking South East Asian gaming scene throughout the latter days of the PlayStation Vita and beyond has brought us a variety of games in English that, ten or twenty years ago, we would have never seen localised for the English-speaking market. And there are a lot of releases that are exclusive to this part of the market — usually to avoid having to tussle with the regulatory boards of the region, and to prevent situations like the unfortunately notorious case of Omega Labyrinth Z.

Like with limited-press versions of games, you may well find yourself having to pay a little bit more to import Asian English versions of games — but they provide the opportunity to have a boxed copy of a game on your shelf that either isn’t available in your home region at all, or which is digital-only at best. It also helps demonstrate to Asian developers, publishers and localisers that there is an English-speaking market for their games.

And, of course, the final piece of the puzzle in all this takes us back to the retro side of video game collecting. While certain parts of the retro market have skyrocketed in value over the years, certain other parts can still be picked up spectacularly cheap. A huge proportion of sixth- and seventh-generation console games (PS2, PS3, Xbox, Xbox 360) can be scored for 50p per game down at your local CEX — Gamecube games tend to be a bit pricier because the system as a whole seems to have become regarded as a lot more “collectible” — and thus it has become very easy to catch up on games from a generation or two ago that you might have missed out on first time around.

The best thing about this is that a lot of the really cheap titles are obscure yet super-interesting games that are real hidden treasures; they often didn’t get much press attention back in the day for one reason or another, yet they provide wonderful, creative experiences well worth exploring — plus yet another way of making your library unique to you, rather than just the same as everyone else’s.

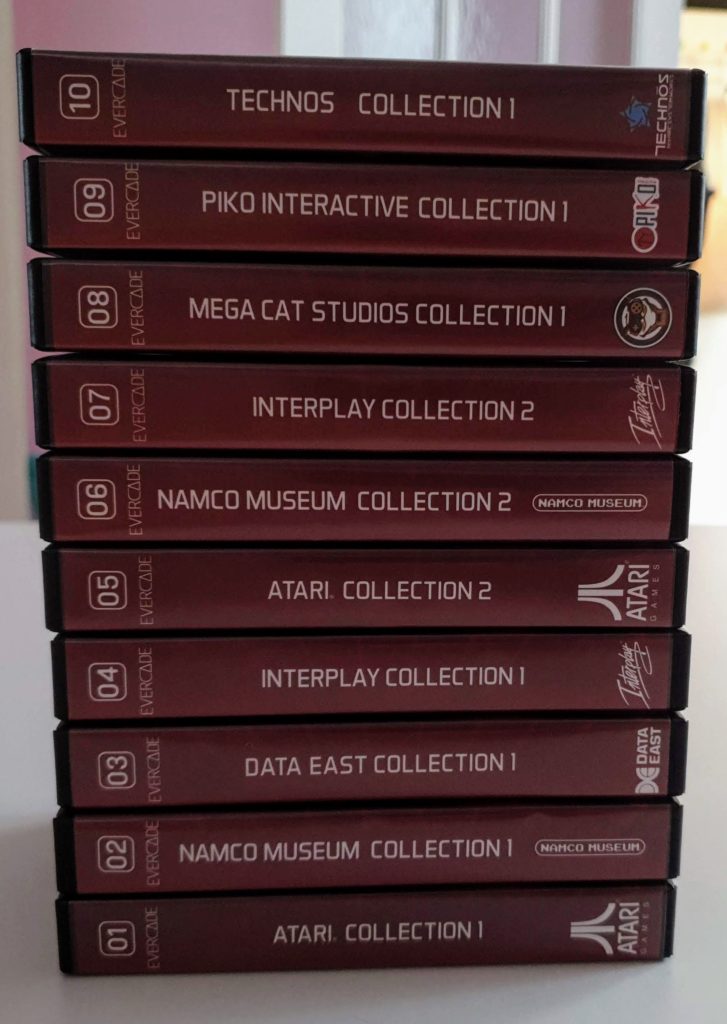

On top of that, there are unique new solutions to the retro question, too — platforms like the Evercade provide a brand new means of keeping physical collecting alive by providing new, officially licensed releases of classic games that, in some cases, have never come west before. This gives a whole new life to games that, in some cases, have gone largely unknown over here for twenty or thirty years — amazing stuff.

So what’s the conclusion?

It all depends on your own priorities when it comes to video game collecting. Retro collections can be amassed relatively cheaply these days if you’re happy to avoid notoriously expensive “cult classics”. New, alternative platforms like Evercade provide a means of collecting retro games without having to seek out potentially decrepit old hardware or physical media. Modern games with widespread releases often drop in price pretty quickly — though you’ll need to consider patch and DLC issues with those. And Limited-print or Asia-English releases provide a fairly affordable means of collecting and celebrating games that otherwise would have ended up languishing in the depths of your downloads list.

As with any hobby, you get out of it what you put in. For the optimal video game collecting experience, you probably need to be ready to spend a bit of money — and usually a fair bit more than you would if you were a digital-only sort of person. But if you care about the long-term preservation of the medium — whether it’s for yourself in the future, or for grander purposes — it’s an investment worth making.

Things aren’t perfect right now, and there’s still work to be done — but on the whole I think it’s a pretty good time to stock up those shelves and build a library.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments below or via the usual social channels!

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023