The supposed rise, decline and revival of Japanese games

Speaking at the 2023 Monaco Anime Game International Conferences, or MAGIC, Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakaguchi reportedly commented on the trajectory Japanese gaming has taken over the years. IGN reported this as the “rise, decline and revival” of Japanese games, noting that “the Japanese gaming turned sour” and has “since revived”.

But this isn’t really accurate, so let’s take a closer look at Sakaguchi’s comments, bearing in mind the broader — i.e. non-mainstream — side of Japanese gaming as well as the “big names” in the development scene.

Sakaguchi noted that he believed the early days of console RPGs had traditionally struggled in the west due to those outside of Japan seeing “pixel art and three-heads-high characters as something for children”. This is an interesting perspective that acknowledges the clear difference in style between western and Japanese games, but it’s not quite correct. It’s perhaps more accurate to say that a lot of these games never got the chance to shine in the west, or in more specific regions.

For example, the original Final Fantasy only came to North America where it was well-received by critics and players alike. It was particularly well-regarded by publications such as Computer Gaming World, who noted that “although it is somewhat dated, [it is] high on the list of games to recommend to people who have no idea what a CRPG is or how to play one”.

CRPG, if you’re unfamiliar, is short for “Computer RPG”, which is a term used to describe classic RPGs for home computers such as the Ultima, Wizardry and Might & Magic series — not only distinct from the console-style approach to RPGs, but also notably different from one another! While these early games in the genre seem quite simple by modern standards, back on their original release they were perceived as quite complex and specialist — so something like Final Fantasy coming along and making the whole experience quite a bit more friendly and accessible was noteworthy.

Where Sakaguchi is likely getting his feeling that console RPGs traditionally struggled in the west is the fact that several installments in his series didn’t make it to English-speaking shores until much later console generations. Notably, Final Fantasy II and III were completely absent from the western NES library, causing the now-infamous confusion that stems from the American version of Final Fantasy IV being known as Final Fantasy II, and Final Fantasy VI becoming known as Final Fantasy III.

Here’s the thing, though: they didn’t really “struggle” as such. I can’t speak for the financials of the games in question, but throughout the 8- and 16-bit eras in particular, RPGs continued to be noteworthy releases that got a significant number of column inches in magazines of the time, and often positive receptions from critics.

These were games that expanded the boundaries of what video games could really be; in contrast to the arcade-style affairs that dominated the early days of gaming, RPGs were sprawling, lengthy adventures intended to be enjoyed over the long term, and that made them particularly noteworthy for critics and players alike.

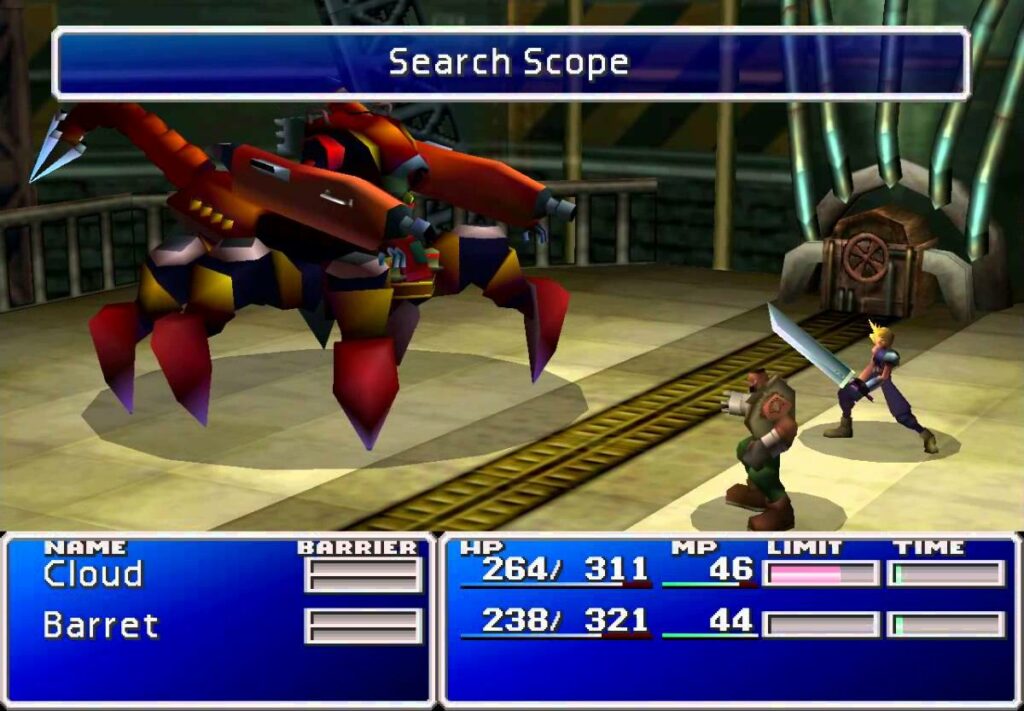

Sakaguchi noted that he believed Final Fantasy truly found its feet in the west “when we were able to incorporate CG for Final Fantasy VII”. This is true to a certain extent; speaking from my own personal perspective, Final Fantasy VII was the first RPG I actually played and understood after years of thinking (erroneously, as it turned out) that the aforementioned “CRPGs” were too complex.

It’s also noteworthy that Final Fantasy VII marked the first time the series came to Europe; while it wasn’t the first console RPG that ever arrived on European shores, it was absolutely one that made a huge splash thanks in part, as Sakaguchi notes, to its impressive visuals.

Sakaguchi’s argument, as reported by IGN, is that Japanese development started to drop off during the PlayStation 3 era due to the changes in system architecture that led to modern consoles being more like custom-built PCs.

“Consoles like the NES and PlayStation were very specific hardware,” he said. “This made it easier for Japanese developers to master the hardware, as we could ask Nintendo or Sony directly in Japanese. This is why — I realise it might be impolite to say this — Japanese games were of a higher quality at the time. As a result, Japanese games were regarded as more fun, but when hardware became easier to develop for, things quickly changed.”

Anecdotally, Sakaguchi has a point here for sure. Speak to a North American who grew up playing Japanese console games on the NES, Mega Drive and the like, and they’ll have a great deal of difficulty coping with western-developed home computer games, particularly those developed in Europe; they’re very much something you had to have grown up with to truly appreciate. But as console generations advanced, the gap between western and Japanese games closed quickly — and, Sakaguchi argues, once developing for console became effectively the same as developing for PC, western developers took the lead.

While Japanese PC games certainly existed, many of these were written for proprietary personal computer platforms such as NEC’s PC-88 and PC-98, the Sharp X68000 and the Fujitsu FM Towns. Meanwhile, in the west, the PC market had been gradually moving from the proprietary home computer market towards the standardised “IBM PC compatible” system that today’s machines are still effectively based on and thus, Sakaguchi argues, western developers had a head start.

Herein lies the point where I question the main thrust of the IGN piece, and this is an argument that we’ve gone over quite a few times in the past couple of decades. As soon as the PS3 era hit, Japanese games didn’t suddenly “die out” in favour of popular western franchises like Elder Scrolls, Dragon Age and Mass Effect. Rather, their audience changed — and, arguably, so too did the intent of their developers.

Japanese games — particularly RPGs — throughout the seventh generation weren’t intended to be blockbusters on the same scale as the aforementioned western titles. Instead, they’re perhaps best thought of in a similar manner to seasonal anime — often developed on a relatively limited budget, and designed with a laser-focused, specific audience in mind rather than attempting to appeal to a broad demographic. As we started to see more capable handhelds such as the PSP and Vita hit the market, this became much more apparent.

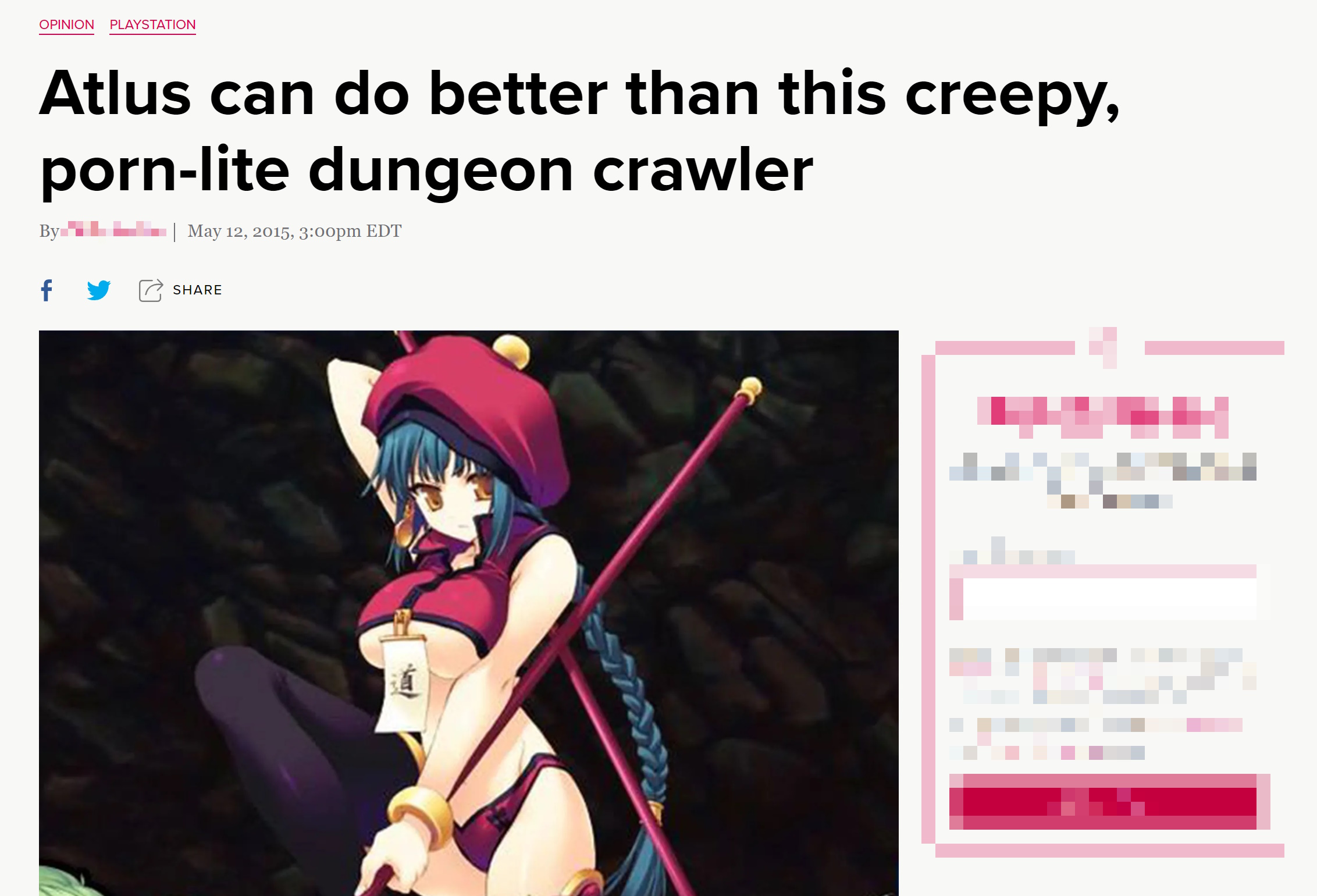

Part of the problem in the west lies with the press. Look back at reviews of RPGs from even the PS2 era, and you’ll often see writers who very clearly didn’t put much time into these games before writing about them. In many cases, the writers make broad, sweeping assumptions — and particularly in the PS3 and Vita era, many reviewers started to become outright dismissive of pretty much the entire genre, particularly once it seemed that audiences had a taste for life on the mildly ecchi side.

Unfortunately, the rise in sexually provocative Japanese entertainment on consoles happened to coincide with the growth in popularity of self-righteously “progressive” viewpoints in the west, leading many critics to seemingly feel obliged to criticise games simply for featuring busty female characters in revealing outfits.

The silly thing about this is that if you look back at many of the games that earned the most ire for all this, not only is the ecchi content ridiculously tame compared to some of the things that are readily available today, but the games themselves often had their own point to make with this content.

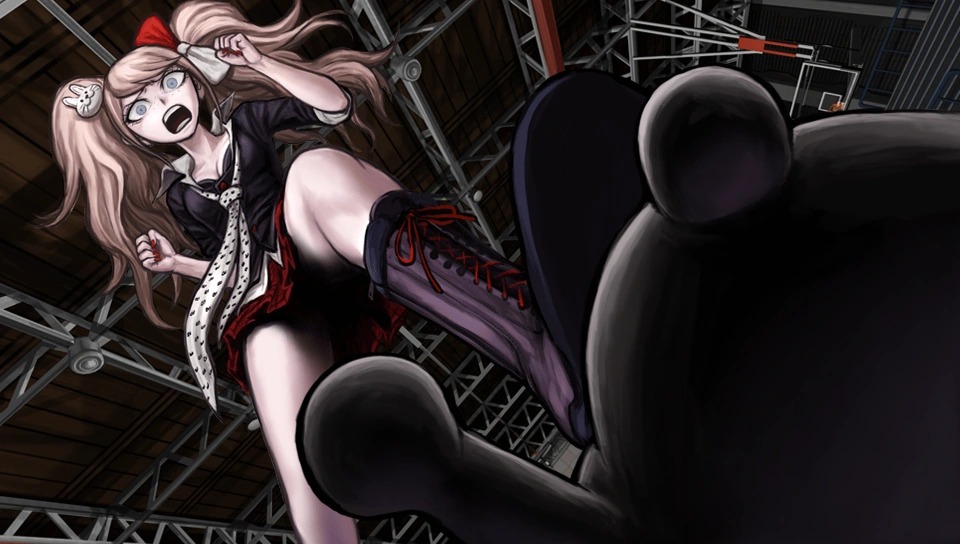

Take something like Vita dungeon crawler Dungeon Travelers 2: The Royal Library and the Monster Seal, for example. This is an absolutely magnificent game; mechanically dense but accessible, full of fun characters, packed with a vast quantity of dungeons to explore (including a post-game that is bigger than the main game) and featuring some thoroughly lovely art throughout. And yet on it being announced for localisation by Atlus, the response from one particular outlet was “Atlus can do better than this creepy, porn-lite dungeon crawler” (see image above).

The daft thing is that if you spend any time with Dungeon Travelers 2 whatsoever you’ll note that 1) its ecchi content is pretty mild and 2) it always has an actual purpose. There are two main functions of the ecchi content, in fact: one, to demonstrate the growing level of affection and genuine bonds between male protagonist Fried and the various young women he surrounds himself with over the course of the game; and two, to crack a joke at the expense of people who lose all reason at the sight of something vaguely naughty.

That last one bears a bit of extra explanation: upon defeating the various “boss” characters in the game (all of whom are cute girls) they’ll inevitably end up in some sort of compromising-looking position. Rather than being depicted as powerless, however, they’re shown attempting to use their sexual wiles to seduce the protagonist — who, as the only male, actually isn’t a participant in combat anyway — and convince him not to seal them away in his magic book. Much of the humour comes from Fried’s near-asexuality in these circumstances; by midway through the game you can feel his frustration as yet another monster girl thinks that showing him her bum will get her what she wants.

It’s easy to look at that on a superficial level and view it as exploitative, and that’s exactly what a lot of western critics did. Unfortunately, that means very few bothered to delve into the game properly and learn that it was actually doing some really interesting things — not just with its provocative content, but in general with its mechanics.

Why bring this up? Because it’s a big part of why Japanese games are perceived to have declined in relevance during this period of gaming history. A lot of publications barely gave any attention to these titles, and when they did, it was often with a dismissive, derisive tone — even in cases where there wasn’t sexual content, such as in Sakaguchi’s own Blue Dragon on Xbox 360. And to this day, western fans of popular media continue to be concerned about western critics’ refusal to engage in a mature fashion with anything containing the slightest hint of sexuality.

But there are exceptions — and they’re seemingly quite unpredictable, too. Take relatively recent breakout hits like Persona 5 and Danganronpa, for example; both of these feature content that particularly prudish critics would typically baulk at, but for some reason both largely escaped the wrath of even the most puritanical of western critics. In both cases, the games are obviously, heavily stylised even beyond their anime inspirations — but it surely can’t be that simple, can it? Anime game bad, anime game with heavy black outlines and high-contrast colour palette good? We may never know for sure.

Sakaguchi remains philosophical about the future of Japanese games, and how they can — and should — remain distinct from western titles.

“In the west, children often get their own room from a very young age,” he said, “while in Japan the whole family sleeps together in the same room. I think that such small cultural differences can be felt through the games we make today. Even when western games became mainstream, I didn’t feel the need to be inspired by them. I believe that cherishing my Japanese cultural background is what attracts people towards my games in the first place.”

And that’s an important point, I think. Many of the Japanese games released during the supposed “decline” of Japanese games are unashamedly Japanese. They feature traditional Japanese cultural elements, character tropes typically seen in Japanese popular media, and presentational and mechanical elements that have historically been popular with Japanese audiences. It’s perhaps quite telling that the Japanese games most commonly regarded to have been “mainstream successes” these days — things like FromSoftware’s output — are those that are deliberately inspired by western aesthetics.

To sum all the above up, I don’t think it’s necessarily that Japanese games have ever really suffered a “decline” as such — it’s more than the audience of gaming as a whole has grown and changed over time, and there is now a much broader range of experiences available for people to enjoy. This, in turn, means that the concept of a “must-play” game doesn’t really exist any more, because if you’re not really into something there are a thousand and one other new releases you can spend your time with instead.

Japanese games, series and developers continue to serve their audiences — and in increasingly unashamed fashion, what with us finally seeing uncut releases of games that once had heavy edits a couple of generations ago. That’s a good thing, and I absolutely don’t think it’s anything for Japanese developers to be ashamed of that Colin Callofduty isn’t engaging with their work any more. Better for the breadth of a medium to serve multiple distinct demographics rather than make a futile attempt to appeal to everyone universally, I say!

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023