The History of Project Zero

Also known as Fatal Frame in the United States and simply 零 (Zero) in Japan, the Project Zero series is one of the great unsung heroes of the survival horror genre.

Originating back on the PlayStation 2, this long-running series has a very distinctive sense of style about it — and if you’re particularly interested in uniquely Japanese views on the supernatural, it should be considered required reading.

With the new port of fifth game Project Zero: Maiden of Black Water dropping tomorrow, we thought today might be a good day to get you up to speed on what the series did prior to this point. We won’t be talking in depth about Maiden of Black Water today — we’ll look in more detail at the new version very soon — but this should give you an idea of what you might have been missing out on up until now!

It’s worth noting that each game in the series very much stands by itself, so if you’re new to Project Zero, you can safely start with Maiden of Black Water. However, if you have the means of playing the older games, you’ll find an even more rewarding experience to explore — as will hopefully become clear by the time we’re done here today. So let’s dive in! Bring a torch.

Project Zero (2001, PlayStation 2)

Project Zero stood out immediately, even on its first release. While 2001 was a time before classic survival horror series such as Resident Evil veered off in a more action-oriented direction, Project Zero still distinguished itself by eschewing the blood, gore and violent scenes people had come to associate with the genre.

Instead, it provided a game with its roots deep in traditional Japanese spiritualism — something which the series has remained steadfastly true to ever since. And, rather delightfully, this original game has held up astonishingly well since its original release 20 years ago.

The intent behind Project Zero, according to director Makoto Shibata, was to provide a game with simpler mechanics than his previous work, the thoroughly unusual “you’re the bad guy” RPG Tecmo’s Deception: Invitation to Darkness. While Deception had engaged players through its complex interlocking game systems, Shibata wanted something more straightforward and primal for Project Zero: he wanted to engage people’s emotions.

Writing on the North American PlayStation Blog in 2013, shortly after the first Project Zero was rereleased on the PS3’s PlayStation Network in certain territories, Shibata noted that the intent was to “emotionally reach out to players and get them to feel things they cannot actually see on screen.”

Shibata admitted that the horror genre was “aligned with my personal interests, since I tend to ‘see’ things every now and then in real life.” He theorised that his “experience of seeing things that weren’t actually there — or noticing abnormal things around me — were some of the fear factors I thought would appeal to the emotional side of the player, if we were able to embed them on top of the adventure side of the gameplay.”

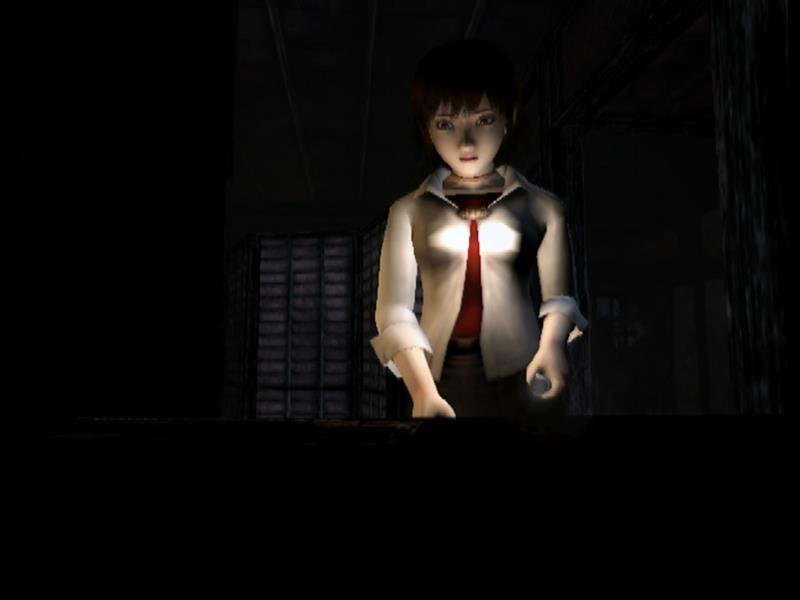

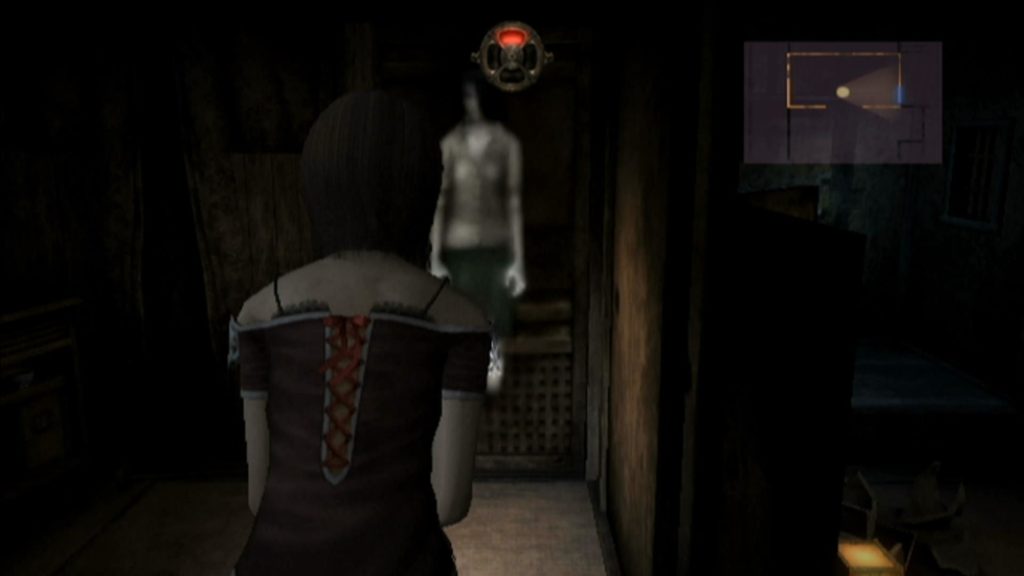

This philosophy can be seen right through Project Zero. The game is deliberately shrouded in darkness and shadows — and the ill-defined things that you can just make out in the middle of that darkness remain consistently terrifying, even if they turn out to be something utterly mundane.

Art director Hitoshi Hasegawa was fairly open about the fact that the original game’s overall aesthetic and atmosphere was heavily inspired by Konami’s classic Silent Hill, but the game eschews that series’ harsh, gritty, dirty industrial look and feel in favour of something much more ethereal; the whole game has a somewhat dream-like feel to it, helped along by the clever use of subtle motion blur and lighting over the course of the game as a whole.

As longstanding horror game fans will know, a critical part of the experience is the use of sound, and sound directly Shigeki Okuda decided that a key part of realising Shibata’s ambition of “feeling things you cannot actually see on screen” would be making good use of stereophonic sound effects.

Indeed, Project Zero’s soundscape gives you a very good idea of where things are in three-dimensional space, and everything from protagonist Miku’s footsteps on the floor to the otherworldly noises the various ghosts make all give you helpful feedback on what’s going on.

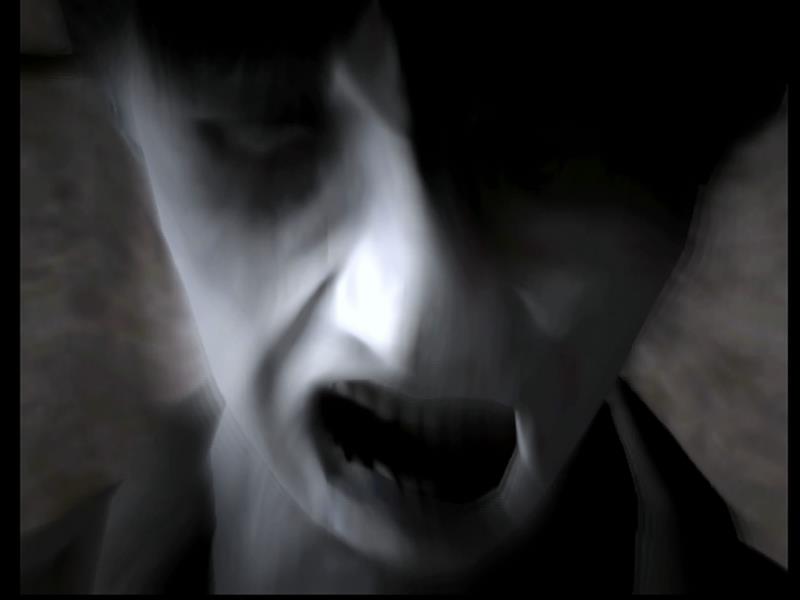

Those ghosts, of course, are Project Zero’s most distinctive, defining characteristic. While other survival horror games of the era pit you against corporeal entities that could be taken down with various forms of physical violence, in Project Zero you were dealing with a much more terrifying threat: the incorporeal forms of vengeful spirits.

The game’s use of ghosts is heavily inspired by Japanese horror films, which in turn take many cues from traditional stories that date back to the 17th century; these tend to combine elements of the supernatural with bits and pieces drawn from folk religion, Shinto and Buddhism. Interestingly, despite deliberately drawing from these established stories, Shibata and company didn’t know much about the specifics of the rituals from these religions — so a lot of things are simply made up, with a few cues taken from the 1970s manga Youkai Hunter by Daijiro Morohoshi.

For example, the “Strangling Ritual” at the centre of Project Zero’s narrative is completely fictional, but it does have its roots in traditional Shinto myths and legends: specifically, the concept of there being worlds other than our own, and various events bringing these worlds into direct contact with one another. This is an immensely popular trope in Japanese fiction, and can be seen in everything from the recent Neptunia x Senran Kagura: Ninja Wars to Final Fantasy XIV via a broad selection of visual novels on the subject.

To say too much would be to spoil matters, however, so let’s turn our attention to mechanics — specifically, Project Zero’s iconic use of a camera for its “combat” sequences.

Since ghosts are incorporeal beings, Shibata and producer Keisuke Kikuchi postulated, conventional combat wouldn’t make a lot of sense. On top of that, they’d always wanted protagonist Miku to come across as a highly vulnerable, fragile character, so it would be equally nonsensical for her to be toting around a variety of heavy weaponry.

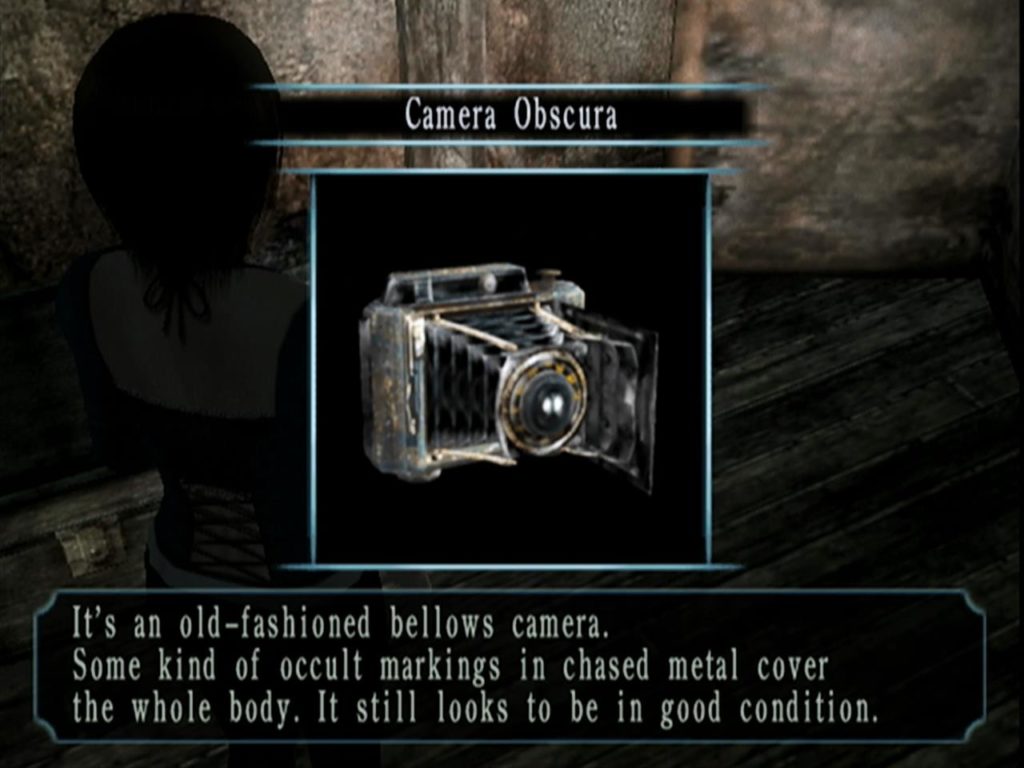

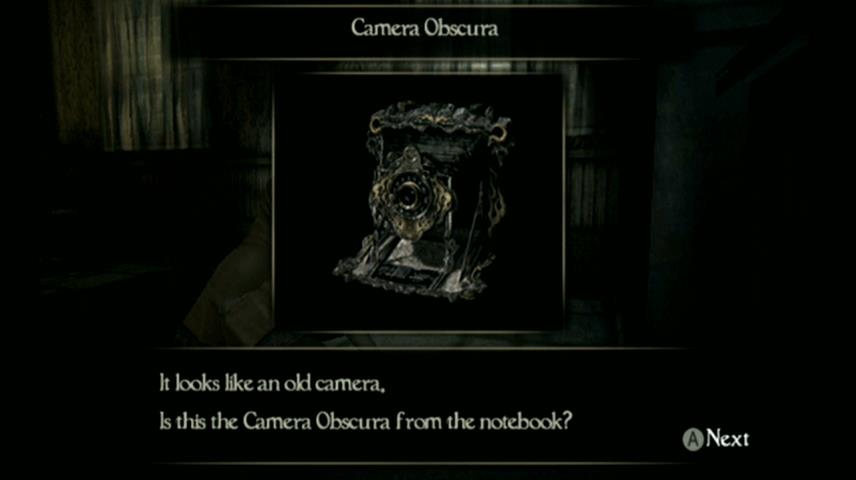

The concept of the Camera Obscura was born, and with it probably the most “gamey” aspect of Project Zero. Rather than being a straight matter of point and click in a first-person shooter style, Project Zero’s combat is instead about careful timing and observation of your foes.

Each ghost has its own distinct movement pattern, including animation and audible cues, and learning to recognise these is an essential part of success in Project Zero’s combat. On top of that, you need to quickly learn how to take advantage of the various “Shutterbug Moment” bonuses it’s possible to acquire by doing things such as centring your sights on a special marker, hitting a ghost while they’re in the middle of an attack and charging up your camera’s mystical power as much as possible.

Interestingly, Project Zero actually has an arcade-style scoring system, with more effective shots being worth considerably more points. This isn’t just for fun, either; your score can be used to upgrade the camera in various ways, and doing so helps make your life a whole lot easier — though combat is still deliberately clunky and cumbersome as a means of deliberately instilling that distinct sense of “survival horror panic” in the player.

You’ll learn to master how to handle the camera as the story progresses — which is good, as a challenging Battle Mode opens up after you’ve beaten it for the first time, and then a Nightmare difficulty, with plenty of unlocks on offer as a reward for exploring the game to its fullest.

This was just the beginning, of course…

Project Zero 2: Crimson Butterfly

The second game in the Project Zero series began development shortly after the first game was completed, and finally showed up for Japanese and North American players in late 2003, with a European version following in April of 2004. Following this, there was an enhanced port to original Xbox in late 2005. It then got a complete remake for Nintendo Wii in the summer of 2012; for some reason, this totally skipped a North American release and instead only came out in Japan, Australia and Europe.

Once again writing on the North American PlayStation Blog, this time to coincide with Project Zero 2’s rerelease as a downloadable game for PlayStation 3 in 2015, Makoto Shibata noted that he and his team took on board plenty of feedback from players of the first game when designing the sequel.

“Players got too scared to complete the game,” he said. “So we shifted our attention to making the storyline more interesting, to encourage such players to overcome the scariness in wanting to see the end of the story.”

Producer Keisuke Kikuchi, meanwhile, was keen to distance the new game from the concept of “action horror”; speaking with Team Xbox in 2005 (the year Resident Evil 4 first came out) he acknowledged that some members of the press had felt the first game was too easy, but noted that the team had no intention to “make it difficult, because this is absolutely ‘horror’, not an ‘action game'”.

Project Zero 2 distinguished itself from its predecessor in a few ways. Firstly, it had a much broader scope; rather than being confined to a single house, the game as a whole unfolded across an entire village, incorporating outdoor areas and more natural environments such as caves. Its Xbox incarnation also featured a mode where you could play the entire game in first-person perspective; Kikuchi regarded this as an attempt to “make the game scarier”, but acknowledged it was more an experiment than an earnest attempt to shift the game to an entirely new perspective.

The Wii rerelease, meanwhile, did shift things around a bit. Since it came out after the Japan-only release of fourth game Tsukihami no Kamen (also known as Mask of the Lunar Eclipse), it adopted that game’s over-the-shoulder third-person view plus a few motion controls that added the potential for additional scares; now you had to physically “grab” objects, and it was entirely possible that ghostly hands would reach out and grab you right back!

The Wii version also fleshed out the plot somewhat with additional narrative material and cutscenes, and also incorporates a strange on-rails “Haunted House” postgame mode, where you have you “fear” level rated according to how steadily you hold the Wii Remote and Nunchuk during the experience.

Narratively, Project Zero 2 is mostly unrelated to the first game, though some minor characters mentioned in the second game showed up as ghosts in the first; since the story of Project Zero 2 canonically unfolds before the events of the first game, this gives us the understanding that they met with some sort of terrible fate in the intervening period.

The game is based on an urban legend that suggests people who get lost in a particular forest find themselves trapped in a “lost village”. This being a ghost story, the urban legend is, of course, true — and twin sisters Mio and Mayu find themselves trapped in the legendary (and ghost-infested) village of Minakami after following a mysterious butterfly.

Naturally, Minakami’s status as a hotbed of supernatural activity is all down to a disastrous failure of a religious ritual — and we’re not talking tea with the vicar here. Once again, the game draws inspiration from traditional folk religions along with Shinto and Buddhist beliefs, particularly concerning the intersection between an “underworld” and our own world.

Project Zero 2 particularly emphasised an aspect of the series’ aesthetic that was established in the first game: the fact that the main characters are designed to be highly feminine, delicate and vulnerable. In Project Zero 2 — and indeed all the subsequent games — this aspect of the protagonists is emphasised through the elaborate, delicate design of their outfits; the fact that playable protagonist Mio is wearing a frilly outfit that leaves her shoulders and back exposed makes her seem especially unprotected from the elements — both natural and supernatural.

Mechanically, Project Zero 2 takes heavy cues from the original with a few tweaks to the balance. Basic damage from the Camera Obscura is now very low, so there’s a much stronger emphasis on the “Shutterbug Moments” — of which there are now more possible variations.

The most major new mechanic is actually the one the game’s American release takes its name from: the Fatal Frame. This is a perfectly timed shot during a ghost’s specific animation, accompanied by a panic-inducing loud chirping noise from the camera and a frantically flashing light. These can be unleashed in combos for devastating effect — and doing so, of course, awards you with a lovely chunk of points you can use to upgrade the camera.

Project Zero 2 also adds equippable addons to the camera, which allow you to customise the way it works in various ways; you can increase its damage, stun or slow ghosts, widen the timing window for Fatal Frame shots or even temporarily make ghosts a little easier to see. There are also plenty of other “game-like” elements in the game designed to keep you interested in replaying once you’ve beaten the story once: there are multiple endings, costumes to unlock, letter grade rankings based on your performance and more.

For many people, this is one of the best entries in the series, and thus one well worth tracking down, whether you play it on PS2, Xbox or Wii.

Project Zero 3: The Tormented

Good horror games are genuinely exhausting; they’re taxing to engage with from a physical and mental perspective. And if Project Zero 3’s finale does not leave you breathless with excitement and panic, you’re made of sterner stuff than I am.

Project Zero 3 first released in 2005 in Japan and North America, with a European version following in early 2006. It marks something of an evolution for the series in a few ways: most notably, it’s quite a bit longer than the previous two games, and in this instance is actually a direct sequel to both of the previous games. Project Zero protagonist Miku plays a major role, but extensive reference is also made to the fate of Project Zero 2’s leading lady Mio.

Knowledge of the first two games is by no means required, mind, but the whole experience is significantly enhanced if you play it in context.

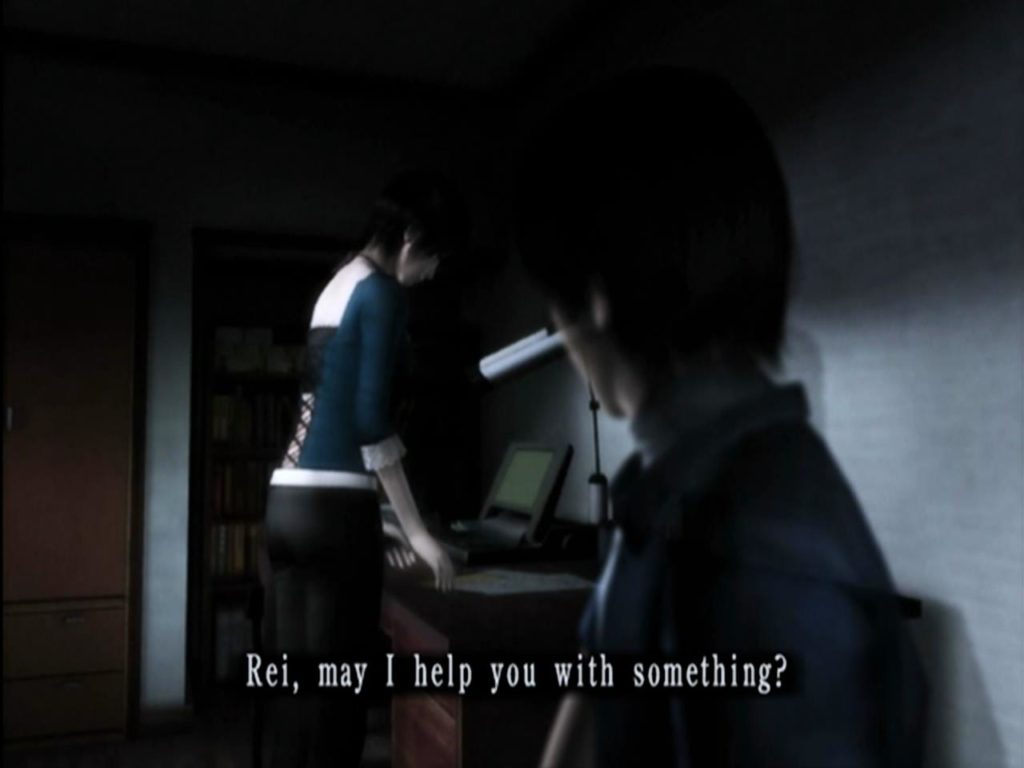

In Project Zero 3, we follow the tale of Rei Kurosawa, a freelance photographer who recently lost her fiancee Yuu in a car accident she believes was her fault. While taking photographs of a spooky old manor that is the source of numerous urban legends, she, of course, ends up cursed — in this instance to suffer recurring lucid nightmares of a “Manor of Sleep” filled with ghosts of the departed.

The curse affects sole survivors of disasters and tragedies, so Miku also found herself affected after the canonical conclusion to the first game; rather than being left alone, however, she was taken in by Yuu and Rei (yes, the combination of their two names meaning “ghost” in Japanese is almost certainly deliberate) since Yuu was a friend of her brother Mafuyu.

To make matters even more complicated, the uncle of Project Zero 2’s leads also gets involved, because he just happens to have been a friend of Mafuyu and Yuu — and was also investigating the mysterious mansion that is the source of the curse. What else is there to do but to team up and get on with some serious ghostbustin’?

“We had the concept of the fear that arises through confronting things you don’t understand,” series producer Keisuke Kikuchi explained in an interview with the writers for the game’s official guidebook. “We gave ourselves the task of making it confusing, thinking it would immerse the player even deeper into the world. While playing, you reason out various things, which I think is interesting.”

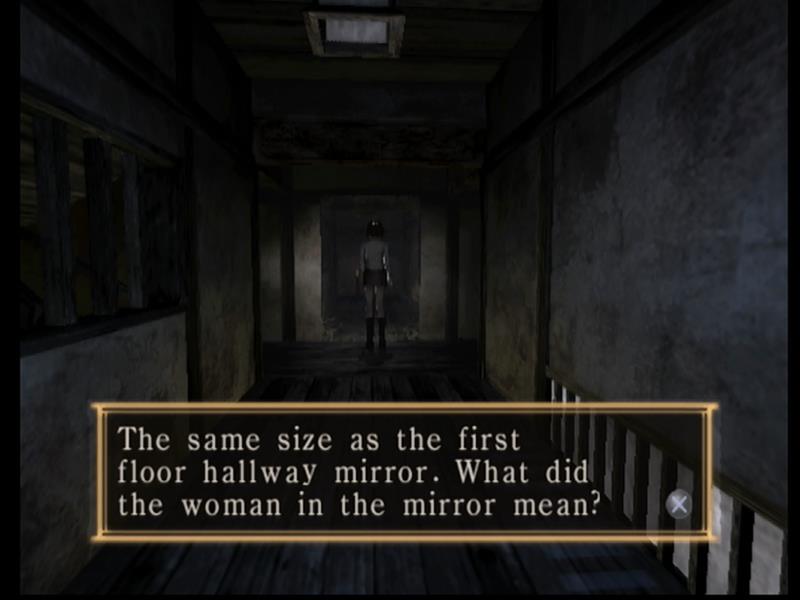

This concept can be seen in terms of how both the player and the characters of Project Zero 3 perceive what is going on. For example, the game’s structure alternates between Rei’s nightmares in the Manor of Sleep and her daily life in her house — but as time goes on, elements of the dream world seemingly start seeping into the real world with varying degrees of subtlety.

The absolute best of these is never pointed out explicitly: there’s an unexplained dark, damp stain on one of the walls of Rei’s house that gradually and subtly expands as the story continues, until eventually it almost looks like there’s a screaming face trapped in it. Spooky!

Kikuchi’s description of the game being deliberately confusing is apt; the layout of the Manor of Sleep initially appears to make no sense whatsoever. There are multiple ways to get to the same place, parallel corridors that look identical but lead to different destinations and rooms that change their layout a little bit each time you visit.

Not only that, but once Miku and Kei become playable characters, you even find yourself visiting locales from the first two games — and if you’ve just come off the back of playing those two, the unexpected ways in which those locations connect with one another will be deeply unsettling!

All this is designed to emphasise the “recurring dream” nature of Rei, Miku and Kei’s struggles; even the most terrifying recurring nightmares can become almost comfortably predictable and familiar the more you experience them. And in Project Zero 3’s case, this manifests itself in the form of shortcuts and alternative routes to get around becoming available, as well as visual clues becoming easier to parse the better you know the layout of the manor as a whole.

The three playable characters aren’t just for show, either; they each have their own unique mechanics for both combat and exploration. The Camera Obscura handles very differently in each of the three characters’ hands, for example, while Miku can also fit through small gaps and Kei is able to move heavy items of furniture out of the way of blocked doors.

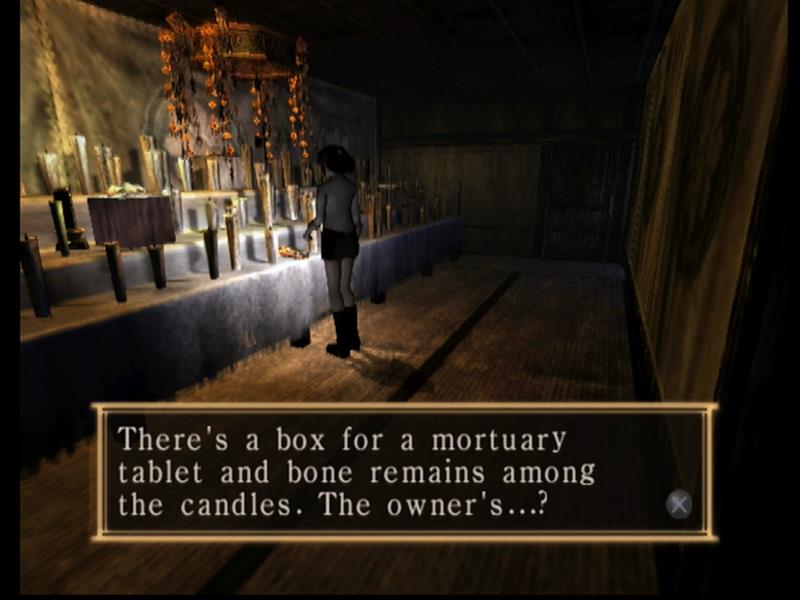

Like the previous two games, Project Zero 3’s narrative stems from a religious ritual that went wrong. In this case, it’s all to do with the concept of a “tattooed priestess” taking on the pain and suffering of others in an attempt to seal the boundary between our visible world and the underworld. It’s an interesting, multilayered narrative — and one of the most ambitious the series had seen up until that point.

“During the game, there are lots of documents,” Kikuchi explained, “But there are also incorrect documents. The books were written with mistakes. They were put in on purpose. They were written based on historical facts, but misinterpreted, and then left behind. They were an element added with the intention of causing confusion. In that sense, it’s not like games these days; it doesn’t show you things in great detail. I wanted there to be things left over that you wouldn’t understand just by thinking about them yourself.”

This feeling of developers trusting the player to “get” what the story is all about without necessarily revealing everything explicitly has proven popular in more modern games that take a similar approach, with FromSoftware’s Souls games being consistently held up as a good example of it being done well. As such, if you like that feeling of being trusted to put in a bit of work yourself, Project Zero 3 is definitely an entry in the series you should consider investigating.

Project Zero 4: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse

Project Zero 4 is one of the best games in the series… it’s just a pity it never came west in an official capacity, but fingers crossed if the Maiden of Black Water remaster does well we might get the opportunity to see an official localisation. In the meantime, there is an impressive, ambitious and successful fan-translation project out there that allows you to patch an original Wii copy of the game — so you can still play this in English.

Project Zero 4 was the first installment not exclusively developed by Tecmo — Suda51’s Grasshopper Manufacture were also involved, as were Nintendo themselves. It was also the first to leave the series’ original host platform of the PlayStation 2 in its original incarnation — and it was also the first to shift away from fixed camera angles in favour of the over-the-shoulder approach the series adopted from thereon.

“All three companies involved in the collaboration have their own unique styles,” producer Kikuchi noted in conversation with the authors of the official guidebook. “So when we put together everyone’s opinions it was a complete and utter mess, but I think it went really well. The Nintendo development staff were really reliable with pointing out parts in the series up until now where we’d been vague or seemed to make light of something, which I think increased the games quality.

“Also,” he continued, “Grasshopper is a company with great technological strength when it comes to characters’ expressions and actions, which I think added a livelier feeling to the game. Us at Tecmo, of course, concentrated on the fear for this entry in the Zero series, going to the very heart of a traditional horror game and tackling it head-on.”

The concept of the game involves three girls known as Madoka, Misaki and Ruka heading to a mysterious island named Rougetsu in an attempt to recover their memories of a time they were kidnapped. As always, a botched religious ritual — in this case, a Shinto dance ceremony known as a kagura — went horribly wrong, obliterating all life on the island in the process and leaving but a dusty trail of clues (and a whole lot of ghosts) for our heroines to discover.

Interestingly, rather than focusing exclusively on the spiritual side of things, much of Project Zero 4’s narrative concerns psychological and medical horror. Much of the early hours of the game concern the protagonists uncovering memories of being treated for a mysterious condition known as “Luna Sedata Syndrome”, an apparently incurable mental illness, and a take on the popular belief that the phases of the moon affect one’s mental state.

As you might expect from a horror game, it becomes clear that “treatment” for Luna Sedata Syndrome became increasingly invasive and horrifying over time — and, of course, this all ends up tying in with the spiritual angle, too. Like previous installments, there’s a complex, multilayered and morally grey narrative to explore — and, taking cues from Project Zero 3, the game doesn’t spell absolutely everything out for you.

Gameplay-wise, Grasshopper Manufacture’s influence on Project Zero 4 is immediately apparent by the relative “snappiness” of its combat compared to its predecessors. Ghosts move quickly, but make use of clearly telegraphed attack patterns. Clearer visual cues make it easier to get those all important Shutter Chance shots. And the Fatal Frame mechanic is still very much present and correct, and just as satisfying as ever.

Notably, part of the game involves an additional character named Choushiro Kirishima, who is a detective investigating the island completely separately from the girls. Rather than wielding a Camera Obscure, Kirishima instead has a flashlight with the power to repel ghosts; consequently, his combat sequence feel noticeably more “actiony” and complement the camera sequences very nicely.

Project Zero 4 also sidesteps an iconic but sometimes frustrating aspect of traditional survival horror: scarcity. Here, you can purchase healing and camera film at any save point, meaning you’ll never end up completely helpless in the dark — though the game structure does counterbalance this by making said save points relatively scarce in their own right. Unlike previous installments, this is all score is used for; camera upgrades this time around are handled by finding gems scattered around the environment — though choose them wisely, since a single playthrough doesn’t provide quite enough of these to upgrade every character to full strength.

Project Zero 4’s narrative is fascinating, well-crafted and immensely scary. And it’s absolutely criminal that up until now we’ve never had an opportunity to enjoy an official release in the west. Here’s hoping that Koei Tecmo follow up Maiden of Black Water with some very serious consideration of how the rest of the series could be resurrected (no pun intended) on modern platforms; this title in particular would be very well received by fans.

In the meantime, though, if you can bag yourself a Japanese copy of Project Zero 4, the fan translation is readily available via the Internet Archive, including full instructions on how to apply the patch under various circumstances. It does not provide the game itself — you’ll still need to get hold of that yourself!

And so you’re almost up to date — but what of Project Zero’s fifth installment, Maiden of Black Water? Well, we’ve gone on for long enough today — but rest assured we’ll be taking a look at that in depth very soon!

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023