I hope Xenoblade Chronicles 3 is as horny as possible

Xenoblade Chronicles 3 is on the way — and it turns out it’s going to be with us a lot sooner than we originally expected. With that in mind, certain people around the Internet have started writing about it — and the ever-predictable “Xenoblade 2 was too horny” nonsense has kicked off again.

I won’t be linking to the specific article I saw shared earlier today because frankly I don’t want to indulge their hatebait with clicks — but I will instead offer a counterpoint, as well as an interesting perspective on the situation that I saw explained and broken down quite recently by a Japanese artist and translator.

That counterpoint is simple. Xenoblade Chronicles 3 should feel as free to be as “horny” as its creators want it to be, and anyone who feels unable to get on board with that should take a look at themselves and exactly why they feel they can’t get on board with that.

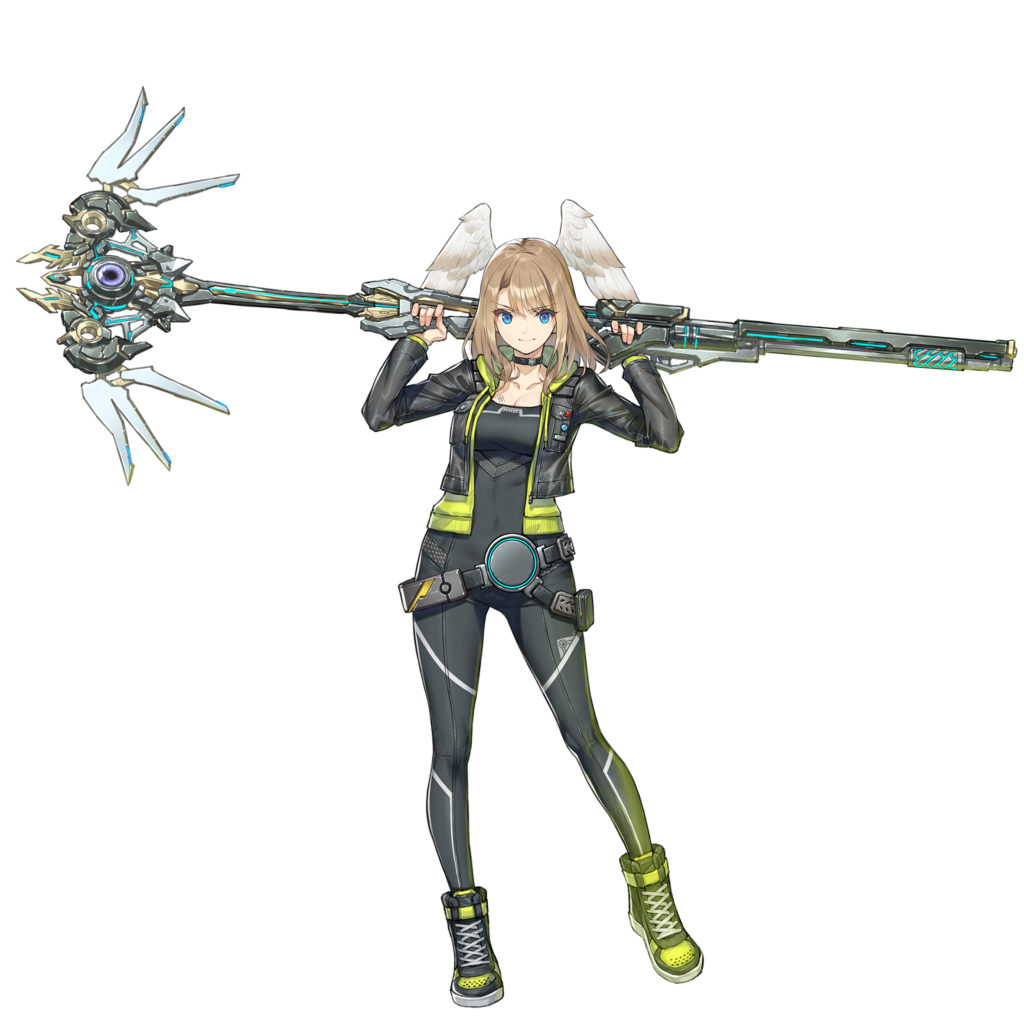

The stupid thing is, compared to many more explicitly ecchi games out there, the Xenoblade Chronicles series has never actually been what I would describe as “horny”, even in its supposedly notorious second installment. Yes, it featured some curvy characters with exaggerated proportions. Yes, Pyra and Mythra’s asses in swimsuits look amazing. Yes, across the entire cast of Blades, pretty much every character- and personality-based fetish in Japanese popular media is catered to in one way or another.

But “horny”? No. Xenoblade Chronicles 2 — much like its predecessors — features some excellent characterisation, rich worldbuilding and provides an incredibly well-crafted experience that you can potentially play for months or even years without seeing everything. Reducing its attractive female characters to being “horny” is, let’s face it, not a great look — because just like in every other instance this happens, it’s not paying any attention whatsoever to the characters themselves, and instead simply judging them by their appearance.

Why does this stupid argument keep coming up? Japanese artist and translator Dan Kanemitsu posted a plausible explanation a few days back, and it’s all to do with contrasting, clashing cultural values over the role of fiction. For the benefit of those who don’t want to sully their browser history with Twitter — I don’t blame you — let’s take a look at his key points.

“The controversy regarding different representations in anime and manga are not just about some people being prudes or obnoxious,” he explains. “I would argue that there is a fundamental difference in how people understand the role of entertainment media including anime and manga. Some think entertainment media is fanciful fiction, first and foremost. Others think media representation in entertainment constitutes a graphic reflection of reality, and that there is a strong interrelationship between the two. These are not mutually exclusive views.”

Nailed it. That’s the core of the issue here, really, isn’t it; the main argument of people who complain about Xenoblade being “too horny” is that it causes people (men, let’s face it) to look at real life women with unreasonable expectations, and to believe that sexualisation is the norm. There are valid arguments to be made in this area, particularly when we’re talking about things like advertisements and supposedly factual content — but the problem is when these same arguments start being applied to completely fictional, obviously fantastic scenarios.

“For those that place strong emphasis on the interrelationship between media representation and social realities, there is no such thing as ‘pure fiction,'” Kanemitsu argues. “[To them,] all representations in fiction are in some way a reflection of reality in one way or another. Others place a strong emphasis on the cathartic qualities of entertainment. Under this school of thought, the fact that the narrative is totally fabricated and fantastic makes it easy for people to project their fears, hopes and other emotions without worrying about transgression.”

In other words, there’s one group of people who believe that all fiction should be an accurate representation of reality — or even a representation of what we should be striving for in reality — while there’s another who believe that fiction is fiction and it can do whatever the fuck it wants because it’s not real. The reality, of course, is that neither of these people are completely right, because the world of “fiction” is so broad that it can fulfil many functions.

“The pure fiction school needs little justification for free speech,” continues Kanemitsu. “Representation needs no justification besides being a representation. So long as no-one was harmed in the production of the work, and if it does not pose a unique threat to real people, no regulation is warranted. The media/reality interrelationship school still seeks freedom of expression, but generally speaking, the right for free speech is a means to an end, namely for the sake of social improvement, curtailing authoritarianism, and safeguarding minority voices that may suffer otherwise.”

Laid out like that, you can hopefully see that both “sides” here have valid points — but neither applies universally to all types of fiction at all times. An explicitly political novel by an anonymous author suffering under a particularly stifling authoritarian regime plays a very different role to a video game about colourful anime people fighting giant monsters for great justice and whatever. This isn’t to say that the latter isn’t capable of saying anything worthwhile and meaningful, either — but that balance between the aspects needs to be taken into consideration.

“This fundamental difference in believe — fiction is good because it’s fiction, versus fiction is tied to reality — alters the perception and expectations that people apply upon anime and manga,” Kanemitsu continues. “In Japan, the pure fiction school is very strong. One of the reasons why the cute moe art style is so popular is because many people like how the aesthetics are a highly refined and distilled form of idealised beauty that most people appreciate as being a total fabrication.”

Here’s the core of the issue: the critics of the “horniness” of titles like Xenoblade seem to believe that obviously fantastic depictions of impossibly beautiful characters — both male and female, let’s not forget — are taken at face value by those who enjoy such media. They argue that by being exposed to such characters, they are developing an unreasonable expectation for people in reality — an expectation which can never be met, because anime girls aren’t real. (Sorry. But it’s true.)

The “pure fiction” school, as Kanemitsu calls it, meanwhile, is absolutely and completely aware that these characters are a “total fabrication” and “a highly refined and distilled form of idealised beauty”. People who appreciate a beautiful anime character aren’t looking for a person in real life to match up to that character; they like that character specifically because they’re an impossibility in reality.

But let’s look at the other side of things.

“In some parts of the west, the media/reality interrelationship school is very strong,” Kanemitsu continues. “This is especially the case with locally created narrative works that involve real life actors and creators. The west has been hard at work trying to redress its history of marginalising certain groups within the entertainment industry and is encouraging their contribution to take a more prominent role. As such, some feel all media should be held accountable to these standards.”

Indeed, there are some valid points here once again. It’s reasonable to argue that a work created in a particular culture should, where appropriate, reflect the true nature of that culture in all its various forms. This is where we get the frequent arguments that “there should be more [people of a particular marginalised group] in [popular series]”. These arguments are usually made with good intentions.

“The desire to redress certain groups can extend beyond encouraging the participation of certain groups and their narratives,” explains Kanemitsu. “[Instead it] can seek to discourage certain groups from stealing the spotlight and create narratives that perpetuate socially undesirable qualities. But from the vantage point of the pure fiction school, projecting real-life social issues upon fiction including anime and manga comes across as unwarranted interference, moral imperialism or even blatant authoritarianism.

“For those in the pure fiction school,” he adds, “demanding fiction heed real life social improvement belies the point of fiction. Fiction such as anime and manga is supposed to be an escape from reality and something people can enjoy guilt-free.”

Again, if we boil down the arguments over Xenoblade’s “horniness” specifically, it comes down to perceived sexism: the assumption that “conventionally attractive and/or sexually desirable female character = sexist depiction”. And yet in the vast majority of Japanese popular media that does feature attractive, desirable female characters, those characters are among the most well-realised and interesting in the cast. It’s rare to see a beautiful female anime character looked down upon for being a woman; in many cases, their beauty even gives them power.

Hell, this is even the case in more realistic Japanese works such as the Yakuza series; attempts have been made in the past to portray this series as being sexist due to its unabashed depiction of the sleazier side of Japanese nightlife — and yet, even amid all that, the women in Yakuza games are often among the most empowered, interesting and well-realised characters out there, even when they’re nothing more than supporting cast members.

“Since no-one can possibly actually marry the impossibly beautiful anime or manga waifu,” Kanemitsu continues, “no-one fights over who owns them. While introducing real-life qualities to anime and manga characters is not something that is rejected, they are fundamentally treated as different representations.”

This is an important point. The existence of beautiful anime characters as pure fantasy does not preclude them from being in some way relatable to the audience, or for their narrative arcs being used to tackle real-life issues in a sensitive manner. Indeed, the best, most beloved visual novels in particular make a point of using their various character routes as a means of exploring relatable real-life concepts through their personal stories.

Their appearance and “horniness” has absolutely nothing to do with it — and indeed for many people may even make the tackling of such issues more approachable and less threatening. Consider if you’d rather talk about the depression and anxiety you’ve been feeling of late with some dirt-encrusted Naughty Dog character who probably wants to stab you, or a sparkling-eyed anime girl with a gentle smile.

“The cute girl moe art style is good for the specific reason that it is so divorced from reality, and people can take solace in their immortality,” Kanemitsu adds. “But for those in the media/reality interrelationship school, the fact that they are an impossibility is at the very crux of the issue. From the media/reality interrelationship school of thought, the construction of an impossible idealised image can be seen as a perpetuation of a socially undesirable stereotype. For that reason, socially undesirable representation should not be tolerated.”

In other words, cute anime girls are good because they’re not real. But they’re also bad because they’re not real. One side of the debate here is fine with the fact that they’re not real; the other side thinks that people will still believe they’re real despite the fact that they’re obviously not. Or, more accurately, they think that they present a skewed representation of reality — when in fact they’re often not intended to reflect reality at all.

“From the pure fiction school, the insistence on the part of the media/reality interrelationship school to encourage certain presentations while rejecting others constitutes a rejection of diversity and hypocrisy,” continues Kanemitsu. “But from the standpoint of the media/reality interrelationship school, the aim to regulate undesirable fiction is out of a desire to encourage diversity that is missing in reality. Not doing this equates to being an accomplice to current social ills and being part of the problem.”

As should hopefully be clear by this point, the whole argument over Xenoblade Chronicles 3 potentially being “horny” or not is utterly stupid for numerous reasons — primarily the fact that even if it is “horny” by certain people’s standards, it by no means precludes it from exploring ambitious, in-depth and well-realised narrative themes and characterisation.

It’s important to accept than in a piece of media like Xenoblade Chronicles 3 — which is deeply, deeply steeped in the well-established and longstanding conventions of Japanese popular media such as anime and manga — impossibly attractive, desirable and even sexually appealing characters are a core part of the appeal. It’s what people hope for and expect from the experience. It’s a fantasy that allows people to escape from our increasingly bleak reality into a wonderful world where everyone is beautiful, the environment is vibrantly colourful, and we can all be the hero.

But, crucially, none of that means it constitutes a complete rejection of the things we need to improve about our own reality. Let people have their fantasy — and let it be as “horny” as the creators of that fantasy want it to be. There’s enough fucking misery in this world as it is, so why on Earth shouldn’t we be able to take the opportunity to hang out with non-existent beautiful people in our own downtime?

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023