If it’s not new, it’s not Final Fantasy

With Final Fantasy XVI just around the corner — and a playable demo hotly tipped to be arriving in the next couple of days at the time of writing — now seems like a good time to ponder something extremely important about the series: one of its core philosophies, in fact.

Speaking with gaming website Gamer Escape in 2016, World of Final Fantasy director Hiroki Chiba noted that series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi’s core ideal for the series had always been “if it’s not new, it’s not Final Fantasy”. And, given that the series’ most recent installments have all been criticised by some based on them not being turn-based RPGs in which players and enemies alike line up politely and take it in turns to hit one another, this is something that it’s extremely important to revisit — particularly given Final Fantasy XVI’s complete embracing of the “action RPG” descriptor.

Final Fantasy is arguably most well-known for its turn-based titles, yes, but it’s also worth bearing in mind that the last traditionally turn-based (well, Active Time Battle-based) Final Fantasy title was Final Fantasy X-2 from 2003. That’s literally twenty years ago.

You’ll notice I don’t count the Final Fantasy XIII series as “traditionally turn-based” despite them technically using a variant of the Active Time Battle system. We’ll come on to that.

With that in mind, let’s run through a brief summary of how each and every mainline Final Fantasy title provided something “new” for the series. Because there really is something brand new in each one, even in those which might appear superficially similar.

In Final Fantasy I, the series began, and helped to establish the formula for the top-down Japanese-style RPG. This was distinct from western-style RPGs in terms of the frequency of combat and the implementation thereof. Heavy inspiration was drawn from the classic Dungeons and Dragons materials — some might say Final Fantasy I outright cribbed from D&D throughout — but the game nonetheless had its own distinct atmosphere and feel which would come to be consistent throughout the 8- and 16-bit titles.

Final Fantasy II shook things up in two major ways: firstly, a massively increased amount of importance in the ongoing story which, although primitive by modern standards, at least makes at attempt to be dramatic and emotionally engaging.

Secondly, its controversial progression system completely ditches traditional experience points and levels in favour of a system where stats and skills increase by you using them. Although often dismissed even by series fans as one of the weaker entries in the series, Final Fantasy II’s mechanics formed the basis of the SaGa series, which is still going strong to this day.

Final Fantasy III introduced the Job system, which built on the fixed classes of Final Fantasy I by allowing players to switch characters between different Jobs according to the situation at hand. Characters would progress both in overall level and Job level independently, making for plenty of interesting decisions to make.

Not only was this an important part of character customisation, but there were also sequences in the game where certain Jobs and their abilities were required to solve puzzles and pass through particular scenarios.

Final Fantasy IV built on Final Fantasy II’s initial work in focusing on narrative by providing us with the series’ most ambitious story to date. While the mechanics are some of the least customisable in the series, with each and every character being locked into a set progression path and your playable party being determined by which story beat you’re on, the story is one of the series’ most widely beloved. Telling the tale of Dark Knight Cecil’s ascension to Paladinhood and his subsequent battle to free the world from oppression, Final Fantasy IV still stands up extraordinarily well as a narrative-based game to this day.

Final Fantasy IV also introduced the Active Time Battle system, which took the series out of strict turn-based territory into something that combined elements of real-time and turn-based. Characters and enemies alike would act based on a “time meter” (invisible by default in FFIV) — when this filled up, it was their turn. The speed at which it filled was determined by both character statistics and effects such as Haste and Slow. This mechanic remained a fixture until Final Fantasy IX, and returned a couple of times after.

Final Fantasy V took Final Fantasy III’s Job system and made pretty much everything about it better. Now it was possible to cross-class certain abilities, so if you had advanced one Job a certain amount you could use its abilities with another Job equipped. The game also wisely ditched the requirement to have specific Jobs in place to progress through certain situations, allowing for complete flexibility in character progression and customisation.

Final Fantasy V remains a popular choice for charity streams, too, with the annual Four Job Fiesta event challenging players to complete the entire game while only using four of the available Jobs.

Final Fantasy VI is, for many, the peak of 2D-era Final Fantasy. Featuring some of the most beautiful graphics on Super NES, one of the best soundtracks of the series and one of the most sprawling, ambitious, epic narratives we’d ever seen in gaming in general, this was a game that pushed not only the Final Fantasy series forward, but the entire gaming medium.

And it still found time for its own distinctive mechanics, this time with characters learning spells according to which “Esper” summonable creatures they had equipped.

Final Fantasy VII took the series into kind-of 3D for the first time, with pre-rendered backdrops and polygonal characters laid atop them. It also leaned hard into a modern setting for the first time; while previous Final Fantasy games had all incorporated elements of sci-fi in one form or another, Final Fantasy VII was the first to be set in a recognisably modern world. I’d say “futuristic”, but in reality, a lot of the more dystopian elements of Final Fantasy VII are regrettably present and correct in our own world today.

Mechanically, Final Fantasy VII’s innovation was Materia, whereby both passive and active abilities could be levelled up independently and passed around between characters in the form of special crystals. Narratively, the game was even more ambitious and epic than Final Fantasy VI was, with its increased production values giving it a “big budget movie” feel and allowing for several of the series’ most memorable dramatic scenes. It also incorporated a variety of fun minigames, both as optional side activities and interactive story moments.

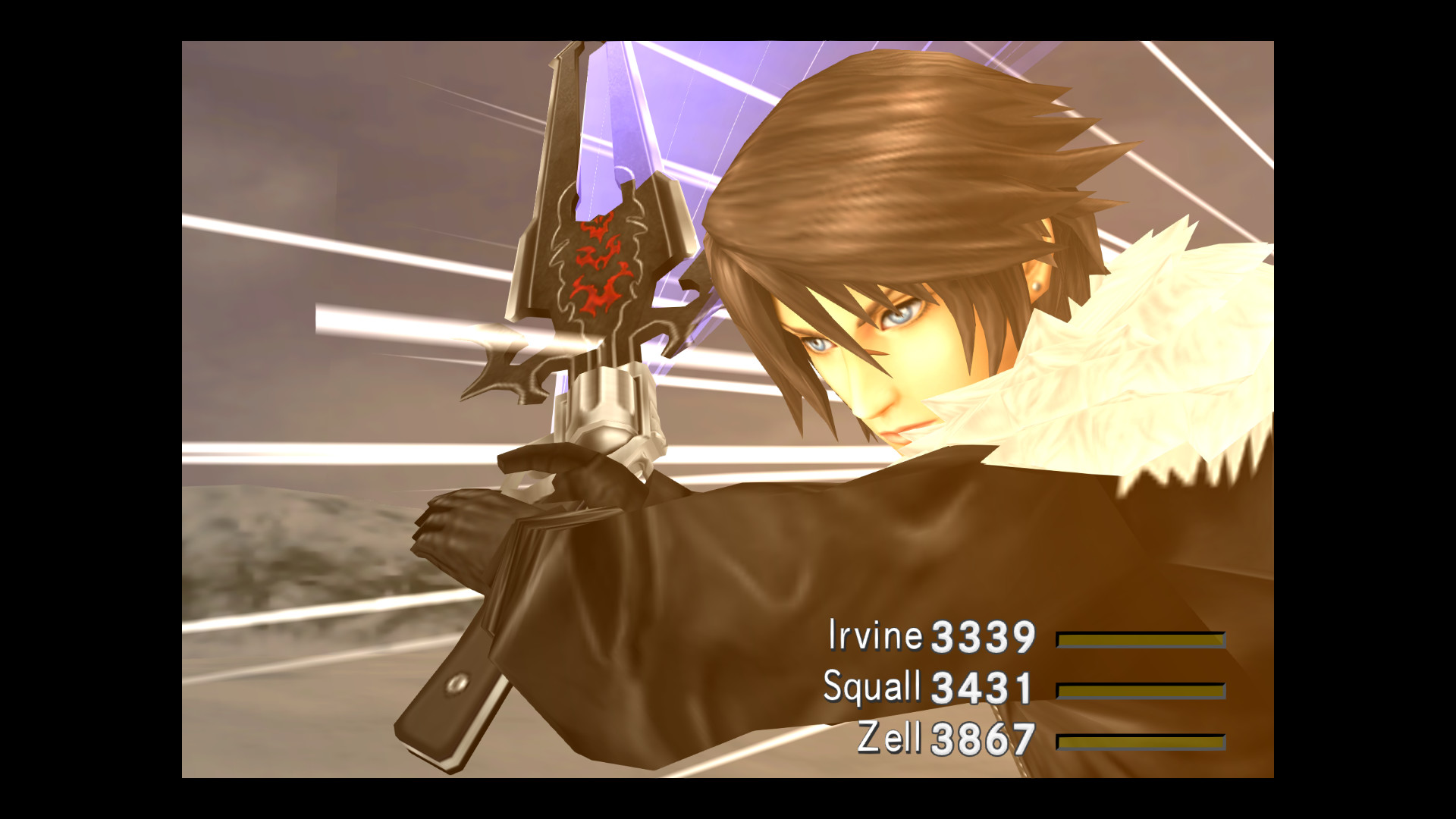

Final Fantasy VIII took the basic polygonal characters atop prerendered backdrops structure of Final Fantasy VII and innovated with its core mechanics. Materia was replaced with the Junction system, whereby spells could be collected like items and attached to various stats in order to power them up — this was controversial in that it made it quite easy to create “broken” characters that were obscenely powerful, but Final Fantasy VIII was more than willing to provide suitable opponents against which you could test these beefed-up cast members.

Final Fantasy VIII also built on the Active Time Battle system with some more interactive real-time elements, including timed button presses and command inputs for certain “Limit Break” special moves. It also brought us the Triple Triad card game, which formed a compelling game-long sidequest — and made a popular return in Final Fantasy XIV.

Final Fantasy IX was always intended to be two things: a fond farewell to the PS1 era, and an homage to the “classic era” of Final Fantasy, meaning, at this point, Final Fantasy I-VI. To that end, the more realistically proportioned characters of Final Fantasy VIII were replaced with a more stylised cast, and the classic “medieval-esque with a few anachronistically modern elements” setting made a comeback.

Mechanically, the game’s main twist was learning abilities from equipment, meaning you’d sometimes have to stick with a “worse” weapon for a while for the sake of learning a particularly useful skill. For many players, Final Fantasy IX represents the ultimate refinement of the Active Time Battle era of Final Fantasy, and it’s hard to argue with that.

Final Fantasy X was the first PlayStation 2 installment in the series, and it was a significant reinvention in many ways. Gone was Active Time Battle, for one, to be replaced with what was referred to as Conditional Turn-Based combat, meaning that the action was for the most part strictly turn-based — but the turn order could be manipulated in various ways. This turned out to be a very influential mechanic; we still see variations on the CTB formula in numerous other non-Square Enix RPGs to this day, with one of the most notable being the Atelier series.

Final Fantasy X also ditched the “world map and location” structure of previous games in favour of one continuous game world, with the entire game essentially depicting an odyssey of running from one end to the other. Late in the game, you obtain the ability to fast-travel back to previous locations easily, but for the most part, Final Fantasy X keeps you constantly moving forward even more so than any other previous entry in the series.

Final Fantasy X-2 was the first direct sequel in the series, since all previous Final Fantasy games had unfolded in their own continuity with no direct connections. It followed up a loose plot thread left by the end of Final Fantasy X, but also completely changed the overall atmosphere of the game. The rather melancholy feel of Final Fantasy X was replace with something altogether more energetic and joyful, which proved to be a rather divisive decision among series fans. It works well, though.

Final Fantasy X-2 also marked a temporary return to the Active Time Battle system, albeit this time around with variable-length time meters according to the abilities being used. Its Dressphere system also provided a fun variation on the classic Job system from Final Fantasy III and V, with mid-battle character switching forming an important part of strategy for tougher encounters.

Final Fantasy XI was the first even online-only installment in the series and, impressively, it’s still running to this day. While many people are hesitant to try this game on the grounds that it was notoriously challenging and required grouping up with other people to appreciate back in the day, today it is much more accessible and even, for the most part, soloable. Mechanically, the game eschews turn-based combat in favour of semi-real time action, with automatic regular attacks at set intervals and special abilities having charge times and cooldowns to use.

Compared to other MMORPGs available at the time, Final Fantasy XI is also a lot more narrative-centric; the game’s mission-based structure allows you to advance the plot at your own pace and spend the rest of your time exploring the vast number of available jobs and optional side content on offer. If you like exploring and experimenting with mechanics, Final Fantasy XI is still a great game to play, so don’t dismiss it just for being an online-only game.

Final Fantasy XII essentially took the good things about Final Fantasy XI and transplanted them into a single-player game, but it still found time to provide its own unique twists on the formula. Combat followed a similar semi-real-time structure to Final Fantasy XI, but as a single player game, it allows you to pause the game to give commands to your party members at any time. It also features a programmable system called Gambit whereby you can set conditions for your party members to perform various actions automatically. Mastering this is key to success in Final Fantasy XII.

Final Fantasy XII is noteworthy from a narrative perspective in that it forms part of a subseries known as Ivalice. This also includes the Final Fantasy Tactics games and cult classic Vagrant Story, and has specific homage paid to it in one of Final Fantasy XIV’s raid cycles.

Final Fantasy XIII took an ambitious story about determinism and wrapped its entire game’s mechanics around it. Naturally, most people promptly misunderstood this completely and complained about it being too linear and restrictive, but take a moment to critically analyse the game’s narrative and how its gameplay features interact with it, and it makes a whole lot more sense.

Although superficially appearing to use the Active Time Battle system, Final Fantasy XIII’s combat is instead about looking at the “big picture” in battle rather than micromanaging individual commands. Success in Final Fantasy XIII’s battles comes through a combination of character progression and careful use of the Paradigm Shift system, which changes the makeup of your party’s classes and abilities on the fly. Again, this remains commonly misunderstood to this day — but play in the way that is clearly intended and there’s some really interesting design at play here.

Final Fantasy XIII-2 was the mainline series’ second direct sequel (unless you count FFXII’s follow-up Revenant Wings, which tends to be regarded as a spinoff) and built on the structure of Final Fantasy XIII. Although still using the Paradigm Shift system for combat, the twist this time around was that you only had two fixed party members: the third slot could be occupied by catchable monsters who could each have specific roles to play in battle.

Narratively, Final Fantasy XIII-2 also feels like it takes a pot-shot at FFXIII’s most vocal critics, too; rather than the mostly linear narrative of Final Fantasy XIII, we instead have a largely non-linear storyline that jumps around through time, space and dimensions, with each “fragment” having its own distinct things to discover.

Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII changed things up again by focusing entirely on Final Fantasy XIII’s main protagonist Lightning. Again, we had a different twist on the non-linear formula, this time by affording Lightning the opportunity to explore the world more freely rather than jumping around in time.

Mechanically, Lightning Returns featured another variation on the Active Time Battle system, but with a strong focus on changing costumes and the Jobs attached to them. This is a largely underappreciated, oft-forgotten entry in the series — but it’s well worth a play if you haven’t given it a chance. It’s genuinely interesting, both narratively and mechanically.

Final Fantasy XIV surely needs no introduction at this point, but just in case: it’s the second online-only installment in the series, and rather notoriously collapsed completely before being totally rebuilt by a new team into the monstrously successful powerhouse it is today. Offering a combination of an incredibly compelling original story, tons of Final Fantasy series fanservice and plenty of high-level, challenging content for hardcore MMO fans, Final Fantasy XIV quickly took over the title of benchmark MMO from Blizzard’s World of Warcraft and hasn’t let go of the title since.

For those resistant to MMOs, it’s worth noting that like Final Fantasy XI, specific efforts have been made to make Final Fantasy XIV’s main story solo-friendly for the most part. There’s still a bit of work remaining to be done for it to be truly completely soloable, but right now you can jump in and play the game as a “Final Fantasy” rather than “an MMO” with confidence, just to enjoy the story and its amazing soundtrack.

Final Fantasy XV took the series in some interesting new directions followed a notoriously troubled development cycle. We had a shift to open-world gameplay, with a significant chunk of the game involving exploring a large and interesting world, completing quests and discovering all manner of things. And, probably most controversially, we had a move to completely real-time combat — though not, as many critics claimed, “Kingdom Hearts combat”.

Instead, Final Fantasy XV’s combat placed a strong emphasis on stances. You’d need to observe enemies to determine whether it was safe to attack or if you should remain defensive, and give orders to your allies to support you and perhaps create those openings for you. Subsequent post-release updates (collected together in the Royal Edition release of the game) allowed you to play as characters other than protagonist Noctis, with each character having their own unique mechanics to experiment with. Despite a shaky start, FFXV ended up in a good state, and is well worth playing today.

Finally, Final Fantasy VII Remake combines elements of Final Fantasy XV and Final Fantasy XII to create one of the best combat systems the series has seen to date. Not only that, but it also became very clear over the course of the game’s narrative that, despite the name, the developers of Final Fantasy VII Remake were not going for a simple, slavish remake of the original; rather, they were taking a more subversive approach, questioning the established canon and opening up some interesting possibilities for future development.

This, of course, made some fans of the original very angry indeed, but assuming the team follows through on the potential established in Final Fantasy VII Remake — which it looks like they will — it looks like we’re going to have a whole new but recognisably familiar experience to enjoy in the long term.

So there you have it. Every single Final Fantasy has done something new and different. And Final Fantasy XVI will be no exception when it finally arrives at the end of this month.

So instead of worrying about whether or not it’s a “real” Final Fantasy if it’s an action game, embrace it for what it is, and enjoy it on its own merits. After all, if it’s not new, it’s not Final Fantasy.

Join The Discussion

Rice Digital Discord

Rice Digital Twitter

Rice Digital Facebook

Or write us a letter for the Rice Digital Friday Letters Page by clicking here!

Disclosure: Some links in this article may be affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on them. This is at no additional cost to you and helps support Rice Digital!

- Letter from the Editor: passing the torch - June 30, 2023

- Super Woden GP 2 is looking promising - June 30, 2023

- Inti Creates is making a 32 bit-style Love Live action platformer - June 26, 2023